1 Scotland’s Rock Art Project (ScRAP)

Participants of the 2018 Rock Art recording workshop, carried out by Dr Tertia Barnett and Maya Hoole, with assistance from Danny Dutton, Nether Glenny, Stirling.

Scotland’s Rock Art Project was the first major research project focusing on prehistoric rock art in Scotland.

It was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and run in collaboration with The University of Edinburgh and The Glasgow School of Art. Our project aimed to work with local communities throughout Scotland to record prehistoric carvings, some over 5,000 years old and carved onto boulders and rock outcrops in the open landscape.

Often called cup and ring markings, these mysterious motifs are found in parts of Britain, Ireland and Western Europe but we know very little about why they were carved and what they meant to the people who created them. Several of these carvings are managed as Properties in Care of Scottish Ministers, such as those in Kilmartin Glen.

A 3D model of the carved stone at Cairnbaan, Kilmartin Glen, Argyll and Bute. © ScRAP

Our overarching aim was to enhance understanding and awareness of these sites. To do this, we recruited and trained local communities across the country to identify and record the rock art and generate a comprehensive database for Scotland.

Data gathered includes quantitative and descriptive detail, drawings, photography and photogrammetry (3D modelling). This work formed the basis of our research. It enabled us to analyse rock art and its contexts, compare carvings from different locations across Scotland and investigate how the carvings have been reused through time.

The project, which ended in December 2021, was successful in improving national and international awareness of this important aspect of our cultural heritage. It has significantly enhanced understanding and added a vast amount of information to our National Record of the Historic Environment that will enable future research, conservation and management of Scotland’s enigmatic rock art.

2 Islands of Stone: Neolithic Crannogs in the Outer Hebrides

The research team returning to Loch Bhorgastail for the final excavation, July 2023.

Crannogs – artificial islands constructed in lochs – are found across Scotland and are commonly thought to date from the Early Iron Age onwards (around 2,700 years ago).

There are over 550 crannogs known in the National Record of the Historic Environment and 170 of these are found in the Outer Hebrides.

Since 2012, discoveries made in the Outer Hebrides have yielded compelling evidence that some crannogs are much earlier in date – perhaps even 2,500 years or more older than previously thought – meaning they would belong to the first farming communities of the Neolithic period.

These new discoveries have revealed amazingly well-preserved ceramic pots and waterlogged worked timbers. Together these sites tell a different, richer story about the life of the earliest farmers on these islands.

Building on a pilot survey and excavations undertaken in 2016 and 2017, a research grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council awarded funding to explore this further.

Called Islands of Stone: Neolithic Crannogs in the Outer Hebrides, this research project began in April 2020 and set out to investigate the character and extent of these artificial islands that appear so commonplace up and down the Outer Hebrides.

Oblique aerial view of Loch nan Cinneachan, Isle of Coll, centred on the remains of an island dwelling on a crannog. The island is man-made and the remains of three rectangular, dry-stone buildings are visible.

Over the past three years, the project has involved desk-based research, fieldwork and excavation, and work has taken place on land as well as underwater. Local community archaeology groups have assisted and taken up the opportunity to visit and record potential new sites.

A pop-up exhibition, in both English and Gaelic, toured the islands publicising the project and incorporated information on a heritage app which was developed for visitors and anyone interested in prehistory.

The project is now in its final stages and the focus is on assessing the results and how these can be communicated more widely. A workshop is planned for April 2024 and several publications are in preparation.

The project is a joint collaboration we are undertaking with the University of Reading and the University of Southampton.

3 Collaborative PhD: Dounreay and society

Oblique aerial view of Doureay Nuclear Research Facility, taken in 2013.

When you think of the history of the Highlands and Islands you rarely think of Britain’s nuclear energy industry. But, away from the oft-told tale of unemployment and depopulation, the 20th century history of the region is one of a vibrant, growing, and quickly modernising society.

To reflect this, a research project by PhD student Linda Ross looked at the impact of the Dounreay Experimental Research Establishment on Caithness in the mid-20th century. The PhD was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council in a collaborative doctoral partnership between ourselves and the University of the Highlands and Islands.

Although not without its problems in the long run, the construction of Britain’s first fast breeder nuclear reactor by the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) was largely welcomed by the local population, which embraced the benefits of more jobs and greater economic prosperity.

At the heart of Linda’s research was whether and how a new type of society was created to support new nuclear industry in Caithness.

One of a series of photographs detailing the progress of the construction of the 50 non-traditional houses for married staff at Dounreay, Caithness, showing chimney completed, dormers up and cloakroom framework in position. UKAEA non-traditional houses, Thurso, WJ Simms Sons & Cooke Ltd. © Courtesy of HES (Sinclair Macdonald & Son Collection).

Our archival collection from Sinclair Macdonald & Son formed the basis of her exploration of the town planning of Thurso during the period. This local architectural firm oversaw the construction of 1,007 houses and other facilities designed to accommodate the large number of nuclear workers who moved to the county, tripling the town’s population.

By the end of the building programme in May 1963, four recognised estates of UKAEA houses had been built in Thurso by Alexander Hall & Son of Aberdeen:

- Castlegreen

- Ormlie

- Pennyland

- Mount Vernon

Rear elevation of one of the 50 non-traditional houses for married staff at the experimental research establishment at Dounreay, Caithness. UKAEA non-traditional houses, Thurso, WJ Simms Sons & Cooke Ltd. © Courtesy of HES (Sinclair Macdonald & Son Collection).

UKAEA housing consisted of A, B and C types, with A being the largest for higher grade staff. It was believed that such staff required accommodation of high standard to both attract and retain them. If a staff member was promoted or their family increased, they became eligible for a larger house.

Accommodating this population stands as an example of quick, complex change, triggered by a technical experiment with enduring social consequences. The UKAEA built houses are now owned privately or by Pentland Housing Association.

To record this heritage, Linda also participated in the photography of Thurso’s built environment; a body of work which is now available on Canmore. Her project shows how in-depth research adds value to distinct architectural collections, and to the records that we hold.

By moving the study of architectural drawings away from the visual towards the social and cultural, Linda offered us a model on which other studies can be based in future.

Isauld farmhouse cottages, built in 1956. Designed by the Nottingham building firm Simms Sons & Cooke, Thurso architect Hugh Sinclair Macdonald celebrated their ‘considerable charm and character’.

Shortly after Dounreay was announced as the site of the fast breeder reactor establishment, the UKAEA bought two neighbouring farms due to their proximity to the site. One of these was at Isauld, 10 miles west of Thurso.

As part of the deal, the UKAEA built a new house for the farm’s owner, and six cottages for displaced farm workers. The cottages were built to the same design as the timber houses erected as part of the first phase of the UKAEA’s construction scheme for Dounreay workers in Thurso.

These were considered ‘non-traditional’ buildings, meaning they were constructed using materials such as concrete or timber and employed elements of pre-fabrication so they could be erected quickly and cheaply; something which appealed to the budget-conscious UKAEA with its requirement to accommodate employees as soon as possible.

‘A-type' house on the Mount Vernon estate, built in the early 1960s. Situated on the east side of Thurso River it consisted of 99 modern ‘all-electric’ units which did not have coal fires so had no need for chimneys.

The Mount Vernon estate was planned with social integration in mind – part of the estate was occupied by UKAEA employees, with the reminder occupied by tenants in houses built by the local authority. The UKAEA houses at Mount Vernon are surrounded by ample green space, following dominant Modernist principles of the period. A ring-road around the estate provides vehicular access to the rear of properties, with the fronts reserved for pedestrian access.

‘B-type’ housing, built in 1960 as part of the UKAEA’s third phase of housing construction.

With three-bedrooms, this house would have originally been occupied by a Dounreay employee at or above executive officer or engineer level. With the exception of the timber housing built quickly at the beginning of the housing programme, it shows the type of construction which the UKAEA settled on for the majority of its scheme, built by Alexander Hall & Son of Aberdeen. It was believed that housing of this quality helped the UKAEA encourage employees to move to the far north of Scotland.

‘C-type’ housing, built in the late 1950s as part of the UKAEA’s third phase of housing construction in Thurso.

These three-bedroomed ‘C-type’ houses would have originally been allocated to either industrial or non-industrial staff graded lower than executive officer. These semi-traditional houses, which incorporated a prefabricated timber frame, brickwork and exterior harling, feature partial timber cladding to add visual contrast to the scheme.

4 Was there a Catholic school architecture?

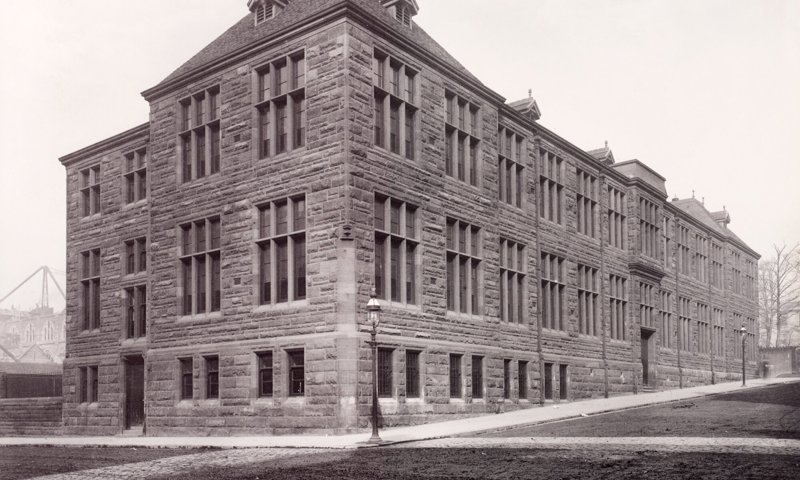

Purpose-built ‘voluntary’ school: view of the newly-built large urban red sandstone St Peter’s Boys School, Glasgow, designed by Joseph Cowan, pictured in 1898.

In 2018, Scotland’s Catholic community commemorated 100 years of local authority-run Catholic schooling since the 1918 Education Act.

The Act saw both the Catholic and Episcopalian churches transfer their church-run schools into public control. Historians recognise the profound transformation of Catholic education following the Act, but what of the school buildings? Were they similarly transformed, and was there a pre-existing Catholic school architecture which was subsequently abandoned?

In 2020 Historic Environment Scotland architectural historian Diane M. Watters authored a report evaluating the impact of the 1918 Education Act on Catholic school architecture and its heritage.

Purpose-built post-war high school: the red-brick and flat-roofed modernist Lourdes Secondary School, Glasgow, by T S Cordiner (1951-7), pictured in 1993.

One of the key findings of the report was that pre-1918 urban Catholic school architecture (adapted or new-built) differed from Victorian ‘Board’ schools.

In the large Glasgow archdiocese, there was an impressive grouping of buildings designed by several recognised Catholic architects, chiefly Pugin & Pugin, but also Joseph Cowan, and Bruce & Hay in the 1890s.

These urban schools were several storeys high, and frequently built of dark red sandstone to harmonise with the churches designed by the same architects.

School building in the east of Scotland was less ambitious, and in Edinburgh, villas and terraced houses were adapted and extended to provide the catholic secondary schools.

However, by 1918 Catholic school buildings were reportedly ‘crumbling’ and the Church was struggling to maintain them. From the 1920s until the early post-war period, the distinctiveness and diversity of Catholic school architecture was still present but in decline.

Our research concluded that by the 1940s new Catholic schools became increasingly indistinguishable from other schools, and by the 1960s, with comprehensive schooling, it became almost impossible to tell Catholic school architecture apart from non-denominational.

But prior to this homogenisation, there was indeed a Catholic school architecture, and much of its heritage survives today for the communities it served to celebrate.

Find out more about the subject of Catholic school architecture by reading the report.