By the Middle Ages, Christianity was the dominant religion of Scotland and had become more organised following the creation of parishes and dioceses (districts controlled by bishops). This led to an expansion in church building giving rich individuals increasing opportunities to use their wealth to influence the design and decoration of these highly visible aspects of Scottish life.

At the very least, this emphasised their faith and status within society, but they also believed that they were fast-tracking their way into heaven through funding communities of priests in collegiate churches to pray for their salvation. They also used their wealth to commemorate family members by adding lavish tombs or stained-glass windows to existing churches.

Memorialising those killed in wartime became increasingly common after World War I. Plaques and monuments paying tribute to those who lost their lives in combat were added to churches and the tradition of an annual Remembrance Sunday service was established.

Dunglass Collegiate Church, East Lothian

Although Collegiate churches like Dunglass can be found from the early medieval period, they were a particular feature of 15th century Scotland.

Scotland’s political rulers – the royal family and those of noble blood - encouraged landowners to build collegiate churches to help counteract the increasing power and wealth of the monasteries by creating religious establishments that were not controlled by the church.

The patrons of collegiate churches funded ‘colleges’ of priests . They were dedicated to praying for the patron and their relatives in the belief that this would speed their souls through Purgatory to heaven.

In some instances, there was a charitable aspect to these types of churches; Dunglass, for example, had a hospital for the poor attached to it.

In the case of Dunglass, after falling into disrepair - following the Reformation in the 16th century - it was converted into a farm building, but much has survived including its stone-slabbed roof.

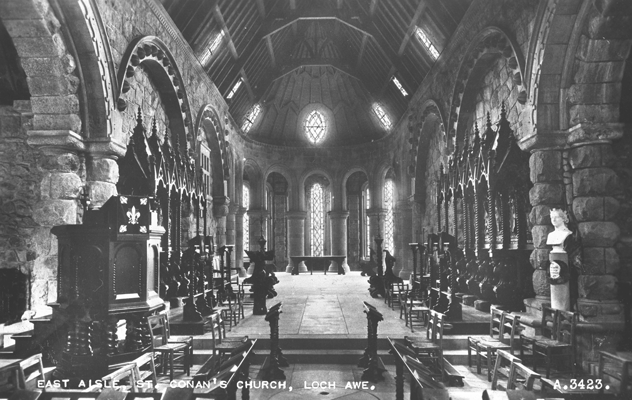

St Conan’s Church, Loch Awe, Argyll and Bute

St Conan’s Church is an unusual example of church design in many ways, not least because its patron designed it himself.

Walter Douglas Campbell had previously constructed a small church close to the island of Innis Chonain on Loch Awe, where he lived with his mother and sister. From 1907 he began work to transform this simple church into an elaborate celebration of Scottish history.

This extraordinary building was designed to include different architectural styles used in religious buildings of all periods, such as Gothic and Romanesque forms, and includes charming details like these rainwater heads shaped like rabbits.

The work was unfinished when Walter died, and his sister Helen spent the rest of her life overseeing its completion.

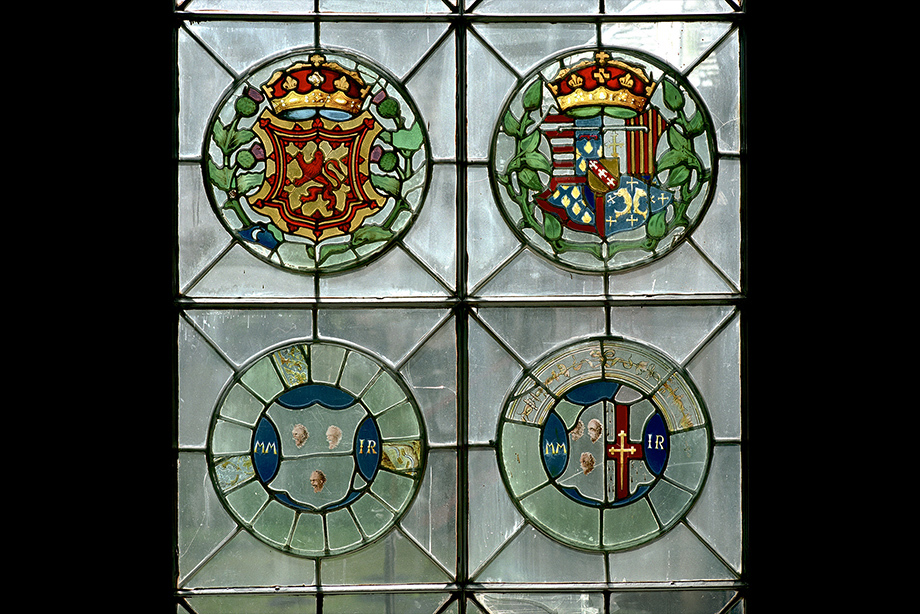

Magdalen Chapel, 41 Cowgate, City of Edinburgh

These glorious decorative roundels contain the only pieces of pre-Reformation stained-glass to remain in their original location in Scotland.

The Magdalen Chapel was built in the 1540s by Janet Rynd. She was the widow of Michael MacQueen who had left a legacy to fund the construction of the chapel and buildings to house a priest and seven poor men.

In return, the men were to devote their lives to praying for the founders and for the infant Mary Queen of Scots. Prayers were also to be said for the Incorporation of Hammermen who ran the chapel and its charitable functions until 1857.

Janet made sure to be commemorated for her role in building the chapel. Starting at the bottom left, the roundels represent the arms of Michael MacQueen, the Royal Arms of Scotland, the arms of Mary of Guise (Regent for her daughter Mary Queen of Scots) and the combined arms of Michael McQueen and Janet Rynd.

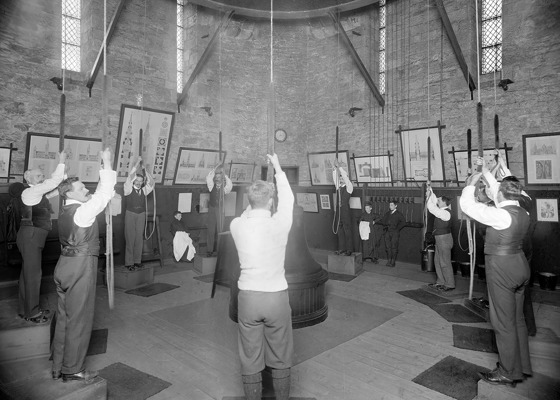

Cathedral of the Isles, Millport, North Ayrshire

Over the centuries, great wealth has enabled individuals to demonstrate and promote their faith in a highly public manner.

In this instance, George Frederick Boyle, later the Earl of Glasgow, was a supporter of the Oxford Movement which campaigned to reintroduce early Christian traditions into the Protestant Church. To encourage this, in 1849 he built the Episcopal College of the Holy Spirit on Cumbrae, an island his family owned.

William Butterfield’s design aimed for maximum impact. The tower rises to three times the length of the nave. This suggests a much larger building when seen from a distance, particularly when arriving by boat. The college became a cathedral in 1876 and it is the smallest in the British Isles.

Crichton Memorial Church, Dumfries

Patrons have played a key role in the funding and creation of places for prayer, whether this be decorative elements, tombs or entire buildings as in the case of the Crichton Memorial Church. This addition to the Crichton Royal Institution was commissioned in 1891 by its trustees in memory of the Institution’s founders.

James Crichton, who had made his fortune in India, richly endowed his widow Elizabeth in his will so that she could fund charitable works after his death.

In 1839 she decided to build, what was then known as, a lunatic asylum. It grew into a virtually self-sufficient community with a world-wide reputation for its approach to quality mental healthcare.

The church took years to finish because care was taken to maintain the quality of design and construction as originally intended. These wrought iron light fittings demonstrate that no expense was spared even with these functional fixtures.

St Peter’s Church, Fyvie, Aberdeenshire

Additions of artwork and extensions to churches are often undertaken in memory of loved ones.

Percy Forbes Leith was only 19 years old when he died of typhoid fever while on active service during the Boer war in South Africa. His family lived near St Peter’s at Fyvie Castle. Percy's father was born nearby and had been able to acquire this impressive baronial building with the fortune he had made running steelworks in America.

When Percy died in 1900, his father’s steelworkers paid the Louis Tiffany factory in New York to make this commemorative window to a design by Frederick Wilson. The Forbes Leith family also funded an extension to St Peter’s to accommodate this beautiful addition to the church.

St Mary's Episcopal Cathedral, City of Edinburgh

Over the centuries, there have been many cases when money has been left to churches or religious communities to fund ambitious building projects.

In this example, siblings Barbara and Mary Walker left their entire fortune to the Episcopalian Church for them to realise their family’s dream of building a cathedral on the site of their childhood garden in Edinburgh.

This fine architectural drawing was Peddie and Kinnear’s unsuccessful entry to the competition which was held to find an architect for the cathedral. Sir George Gilbert Scott won the competition with an alternative Gothic design.

Construction began in 1874 and, by the time the church was completed five years later, it became the largest religious building to be erected in Scotland since the Reformation.

So much money was left after the cathedral was built that, in 1899, the remainder was used to set up the Walker Trust to award grants for ‘the advancement of religion’. The trust was not the only legacy of the sisters as the striking cathedral building still dominates Edinburgh’s western skyline today.

Places for Prayer continued

Consider why sacred sites have long been held as important fixtures in communities throughout Scotland.