The story of women’s access to education and the workplace in Scotland is rich and complicated.

Until 1892, women at Scottish universities could not receive a degree. Today, while more students than ever identify as women, less than 30% of students studying Science, Technology, Engineering and Medicine (STEM) subjects are women.

There are many women who have made groundbreaking achievements in the sciences and medicine over the centuries, but still very few of them are remembered for their contributions to Scottish history.

Although there is much still to be done today, these women are a few amongst many remarkable trailblazers who helped pave the way for equal rights, access to higher education and access to the workplace.

Sophia Jex–Blake and The Edinburgh Seven

The "Edinburgh Seven" were the first women to study medicine at any UK university.

The pioneering group was made up of Isabel Thorne, Edith Pechey, Matilda Chaplin, Helen Evans, Mary Anderson and Emily Bovell and led by Sophia Jex–Blake.

Together they fought to allow women to qualify as doctors in Britain.

Their story began in 1869 when Jex–Blake applied to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh but her application was denied because the university could not justify making changes just for one woman to study.

Undeterred, she advertised in the national press for more women to join her to fight for the right to study. Later that year Edinburgh University became the first British university to admit women.

“It is a grand thing to enter the very first British University ever opened to a woman, isn’t it?”

Academic Discrimination

Despite this victory, the women had separate classes and faced higher fees because their classes were smaller. But they excelled academically.

However, this didn’t see end to their discrimination.

When Edith Pechey achieved the highest marks in her chemistry year she was entitled to a scholarship. The professor charged with awarding the scholarships was so worried about the growing hostility to the women, the scholarship was instead awarded to a lower scoring man.

The Surgeons' Hall Riot

The women were regularly harassed and intimidated. This behaviour came to a head in the Surgeons' Hall Riot in 1870.

When they arrived at the Surgeons’ Hall to sit their anatomy exam the women were blocked by a crowd of several hundred. Pelted with rubbish, insults and with the gate shut in their faces they only escaped when supportive male students and janitors escorted them inside.

However, the protesters did not stop and a group of male students even let a sheep loose in the examination hall to disrupt the Seven.

The outcome was not the one the protesters had hoped for. The story made its way into the national press and such was the outrage they gained influential friends and sympathisers, including Charles Darwin.

Can’t Keep a Good Woman Down

Despite widespread support, in 1873 the Court of Session upheld the university’s decision to refuse the women degrees, ruling they should never have been admitted in the first place.

Determined, five of the seven went on to gain medical degrees from European universities. They worked around the world, founding and working in educational institutes and remaining supporters of women’s rights.

Sophia Jex-Blake returned to Edinburgh in 1878 as the city’s first female doctor. She set up the Grove Street Clinic, which evolved over the years into Bruntsfield Hospital and the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women, before retiring with her same-sex partner Margaret Todd.

In 2019, the University of Edinburgh posthumously awarded all seven women the degrees they had fought for in life. A commemorative plaque can be found to the women outside Surgeon’s Hall in Edinburgh.

Mary Somerville (1780 – 1872)

Before Mary Somerville, the word “scientist” was almost unheard of.

She was no “man of science”, but her achievements in chemistry, astronomy and magnetism, and her passion for mathematics required a new, gender-neutral term. Philosopher William Whewell coined the term “scientist” to describe her.

Somerville was born Mary Fairfax in Jedburgh in 1780 and raised at the family home in Burntisland, Fife. She developed an appetite for learning from a young age, but her family disapproved of her intellectual pursuits, preferring her accomplishments to be appropriate for a young lady.

As an adult, however, Mary was able to devote herself to academic pursuits. She received great encouragement from her second husband.

Listen to 'Learning Latin'

Although Somerville's family disapproved of her intellectual pursuits, she claimed to be "never happier in my life" than the months she spent at Jedburgh, learning Latin with her uncle. Listen to Somerville's memories.

An Astronomical Woman

In 1831, Mary Somerville published Mechanism of the Heavens to great acclaim, followed by On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences in 1834. The work included a mathematical prediction of a yet undiscovered planet orbiting Uranus. Her calculations inspired John Crouch Adams to search the skies for Neptune, which was discovered in 1846.

She would go on to publish another three books including her Personal Reflections.

Somerville moved in the leading scientific and artistic circles of her time. She tutored Ada Lovelace, who is considered the first computer programmer, and was a great advocate for women’s education.

“I resented the injustice of the world in denying all those privileges of education to my sex which were so lavishly bestowed on men.”

Remembering Mary Somerville

A lifelong liberal, Somerville refused to take sugar in her tea in protest to the Transatlantic Slave Trade. She was also the first signatory on John Stuart Mill’s unsuccessful petition for women’s suffrage in 1868.

Somerville received numerous honours before and after her death. She was one of the first women to be made honorary members of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1835 and even received a civil pension from the British Government.

Her name is borne famously by Somerville College, Oxford, as well as a lunar crater, an asteroid, a ship and even an island in Canada.

In 2017, she was honoured with a commemorative plaque at 53 Northumberland Street, Edinburgh, from Historic Environment Scotland.

Elsie Inglis (1864 – 1917)

Dr Elsie Inglis was a pioneer of medicine, a heroine of the First World War, a prominent suffragist and founder of some of Scotland’s first dedicated healthcare for women.

She was born in India in 1864 where her father worked for the East India Company, despite his opposition to Britain’s imperialist policies. When he retired in 1878, the family returned to Scotland.

In 1886, Inglis attended Sophia Jex-Blake’s Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women but left in 1889.

Inglis continued her studies at Glasgow Royal Infirmary before setting up a rival medical school, the College of Medicine for Women at 30 Chambers Street, Edinburgh.

Inglis later worked as a house surgeon London and gained midwifery experience in Dublin.

Healthcare for Women, By Women

Inglis was greatly troubled by the lack of specialised care for women. She established a small maternity hospital on Edinburgh’s High Street for the poor. It was staffed entirely by women.

Known as “the Hospice”, it soon provided training for midwives as women were still not allowed to take up posts in Edinburgh’s maternity hospital.

In 1905, she accepted a post at Bruntsfield Hospital. Five years later, the Hospice amalgamated with Bruntsfield Hospital under her direction.

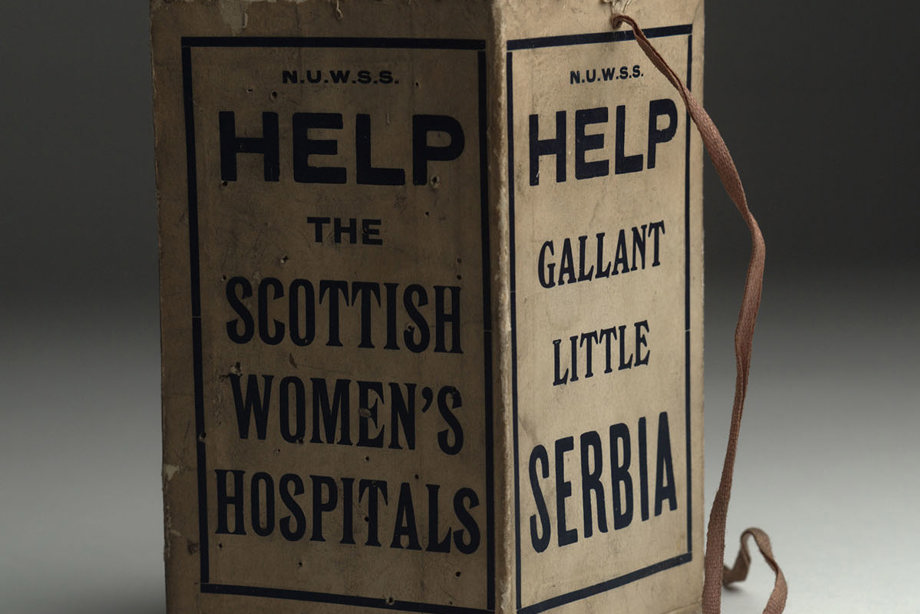

“Go Home and Sit Still”

When the First World War broke out, Inglis approached the War Office to offer her services. She was patronsingly told “my good lady, go home and sit still.”

In response, she established the Scottish Women’s Hospital for Home and Foreign Services and offered her services to Britain’s allies. Many women volunteered, keen to assist with the war effort.

Inglis herself spent time in France, Serbia and Russia battling primitive conditions, endemic disease, capture and ill health. She was held in such high esteem in Serbia she was a awarded the Serbian Order of the White Eagle (1st Class) in 1916.

In 1917, she grew increasingly ill and on 26 November she died of cancer. She was awarded another four medals, before and after her death.

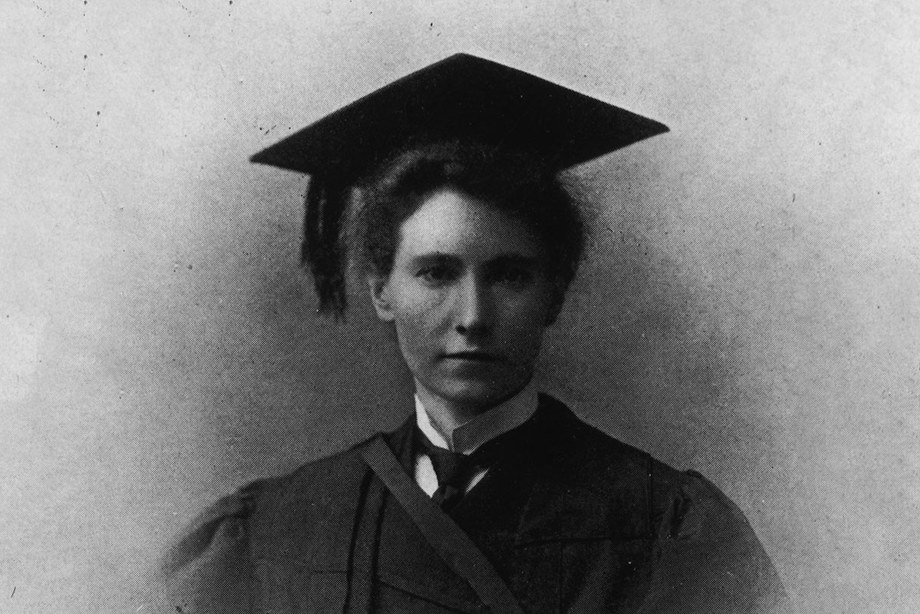

Marion Gilchrist (1864 – 1952)

Suffragist and doctor Marion Gilchrist was born on her family’s farm in Bothwell, Lanarkshire.

In 1890, Gilchrist enrolled in the new medical school at women-only institute Queen Margaret College. It had been named for Saint Margaret and merged with the University of Glasgow in 1892.

In July 1894, Gilchrist became the first woman to graduate from the University of Glasgow and the first woman to qualify in medicine from a Scottish University.

She began her successful career as a GP almost a decade later, setting up a surgery at 5 Buckingham Terrace, Glasgow, where she remained until her death. She specialised in eye disorders and served as an ophthalmic surgeon at various Glasgow hospitals.

Women’s Rights

Gilchrist was a passionate suffragist.

Alongside her medical career, she became a founding member of the Glasgow and West of Scotland Association of Women’s Suffrage in 1902. Gradually, she joined more radical movements, regularly chairing meetings, and in 1909 she declared the campaign to be "the greatest battle of modern times".

Gilchrist continued to be an advocate for women’s rights for all her life.

She died in 1952 and is buried in the Glasgow Necropolis next to Glasgow Cathedral. She left a bequest to Glasgow University and in 1952, the Marion Gilchrist Prize was established for the "most distinguished women graduate in medicine of the year".

Dr Christina Miller (1899 – 2001)

The remarkable scientist Christina “Chrissie” Miller was born in Coatbridge in 1899.

Her hope to become a teacher was dashed when her hearing was progressively damaged from childhood measles and rubella. Despite this disability, she decided to pursue analytical chemistry.

In 1917, Miller simultaneously began studying at Edinburgh University and Heriot-Watt College (now University). She became one of the few women to hold a degree from Heriot-Watt at this time and she graduated from Edinburgh University in 1920.

Miller applied for a PhD under Sir James Walker, a Professor of Chemistry in Edinburgh. He advised her to return after she had learned German, in order to read the leading research. Miller delivered, studying during her daily commute.

She was awarded her PhD in 1924, aged 25.

Miller’s Discoveries

The University’s chemistry laboratories were still under construction in 1921 when Miller began her PhD, making working conditions difficult. However, she persevered, even learning how to blow glass to make her own equipment.

The chemist worked on phosphorus trioxide, producing the first ever pure sample in 1928. Her dedication to her work was rewarded when she achieved her ambition of becoming a Doctor of Science (DSc) before she was 30.

In 1930, a lab explosion cost her the sight in one eye. Now partially deaf and partially blind, Dr Christina Miller remained resolute.

She changed her research to techniques in microanalysis and during the Second World War, she worked with the War Office on rapid gas detection.

Remembering Dr Christina Miller

Dr Christina Miller was held in high esteem and, in 1949, she became the first female chemist to be elected to a fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

The University of Edinburgh named their new teaching chemistry within King’s Buildings laboratories after her in 2000 and set up a Research Fellowship in her name in 2016. Heriot-Watt and the University of Edinburgh have both named buildings after her.

She retired in 1961 after a remarkable career and passed away in 2001 at the age of 101.

Isobel Wylie Hutchison (1889 – 1982)

Isobel Wylie Hutchison was an Artic explorer, author and botanist.

She was born at her family’s estate of Carlowrie in 1889 near Kirkliston. Living a sheltered life in her youth, she would compose poetry on long solitary walks.

Hutchison made her first Arctic expedition when she visited Iceland in 1924. While there she decided to make a long and perilous walk across country from Reykjavik to Akureyri.

Despite being advised against it, Hutchison completed the walk and wrote about her experience for National Geographic, beginning her career.

In 1927, Hutchison visited Greenland as a botanical explorer for the first time. She returned the following year to live in the village of Umanak where she learned about the indigenous people, their native language Greenlandic (or Kalaallisut) and their culture.

A Lifetime of Exploration

Hutchison also collected artefacts and plants on her expeditions. She donated many to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Edinburgh and Kew, and the National Museum of Scotland, including a model of an oomiak she had commissioned herself.

In 1933, Hutchison travelled around the north coast of Alaska, finally completing the difficult journey by a dog team.

Not only a writer, Hutchison also shot footage on her journeys, which is some of the earliest surviving documentary film which is cared for today by the National Library of Scotland.

She received many honours in her life and was the first woman to be awarded the Mungo Park medal by the Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

In 2020, she was awarded a commemorative plaque.

Isobel Gunn (1781 – 1861)

The first European woman to reach western Canada was born in Tankerness, Orkney, in 1781.

In 1806, she made a life changing decision, joining the Hudson’s Bay Company. As only men could work for the company, she assumed her father’s name ‘John Fubbister’ and disguised her true identity.

Apparently unaware of her sex, Gunn’s employers put her to work as a laborer at Fort Albany on the west coast of James Bay. She often worked with a fellow Orcadian, John Scarth, and records state that Gunn worked "willingly and well".

She was capable of a very physically demanding role in hostile conditions and even earned a pay rise.

On 29 December 1807 Isobel Gunn took ill and requested to remain in the house of the trading post’s master, Alexander Henry.

“…he stretched out his hands toward me, and in piteous tones begged to me to be kind to a poor helpless, abandoned wretch, who was not of the sex I had supposed, but an unfortunate Orkney girl, pregnant, and actually in childbirth.”

Return to Scotland

Gunn gave birth to a boy, who she named James Scarth, after John who she claimed was the father.

The company’s policy barred her from any physical labour. Although she had already proven she was more than capable of the work her male counterparts undertook, she was set to work as a washerwoman.

In 1809, Gunn was sent back to Orkney against her wishes. She lived in Stromness with her son where she worked as a mitten maker until her death in 1861.

We don’t know why Isobel Gunn wanted to work for the Hudson’s Bay Company. She may have been lured by the thought of adventure or the prospect of earning more than she ever could as a woman on Orkney.

Her unusual story and defiance of gender rules led to a surprising first for women’s travel.

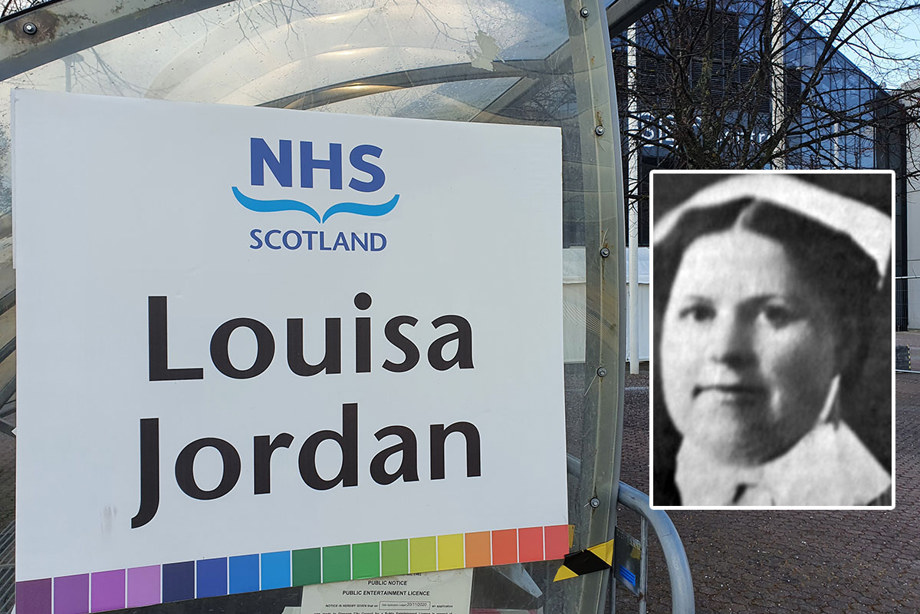

Louisa Jordan (1878 – 1915)

While she was little remembered before 2020, Louisa Jordan’s name became well-known when a temporary hospital in Glasgow established in response to the COVID-19 pandemic was named after her.

Jordan was born in Maryhill, Glasgow, in 1878 to Irish parents.

After she qualified as a nurse, Jordan worked in several hospitals, including Shotts Fever Hospital. Eventually she moved to Buckhaven, Fife, where she was employed as a Queen’s Nurse at the outbreak of the First World War.

A Military Medical Role

Jordan joined the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for the Foreign Service (SWH) in December of that year and entered the 1st Serbian Unit under Dr Eleanor Soltua. Although there was minimal fighting where they were posted in Kragujevac, the unit still had to contend with crude facilities and a shortage of medical supplies.

When typhus broke out in February, Jordan was put in charge of the new typhus ward because of her experience in Shott’s Fever Hospital.

Sadly, Jordan herself succumbed to typhus and died on the 6 March in 1915. She is buried in the Chela Kula Military Cemetery in Niš.

Louisa Jordan, along with other medical staff who served in the typhus epidemic, are remembered annually in Serbia.

Lady Margaret Moir OBE (1864 – 1942)

Born Margaret Bruce Pennycook, Lady Moir was an employment campaigner and one of Scotland’s first woman engineers.

Born in Edinburgh in 1864, she grew up in Dalmeny where her father worked as a quarry master. During the First World War, large numbers of women working in munitions factories did not get time off. She organised a relief scheme so workers received weekend breaks.

Lady Moir was a supporter of women taking up professions. Observing the lack of peace time opportunity for women to pursue a career in engineering, she arranged courses for women and founded the Women’s Engineering Society in 1919.

An early member of the Electrical Association for Women, she also sponsored an all-electric flat for women.

In 1920, she was awarded an OBE.

Christian Maclagan (1811 - 1901)

Christian Maclagan was a talented archaeologist and antiquarian.

Born on a distillery near Denny, Stirlingshire, in 1811, she learned Latin, French, Greek and Gaelic, along with some Italian. She was largely self-taught in archeology.

Maclagan was among the earliest women to publish her own antiquarian research from 1870 onwards, and her energy in visiting so many ancient monuments was astonishing.

But she could not present her papers the prestigious Society of Antiquaries of Scotland because of her gender. Maclagan relied on proxy speakers to read out her script to the all-male meetings.

The status of "Lady Associate" was created by Society of Antiquaries of Scotland for Maclagan and the poet Lady John Scott, as an acknowledgement of their contributions to Scottish heritage. But, perhaps frustrated by not being welcomed as a full member of the Society, Maclagan sent her collection of rubbings to the British Museum instead of Edinburgh.

She was awarded a Historic Environment Scotland commemorative plaque in 2018.

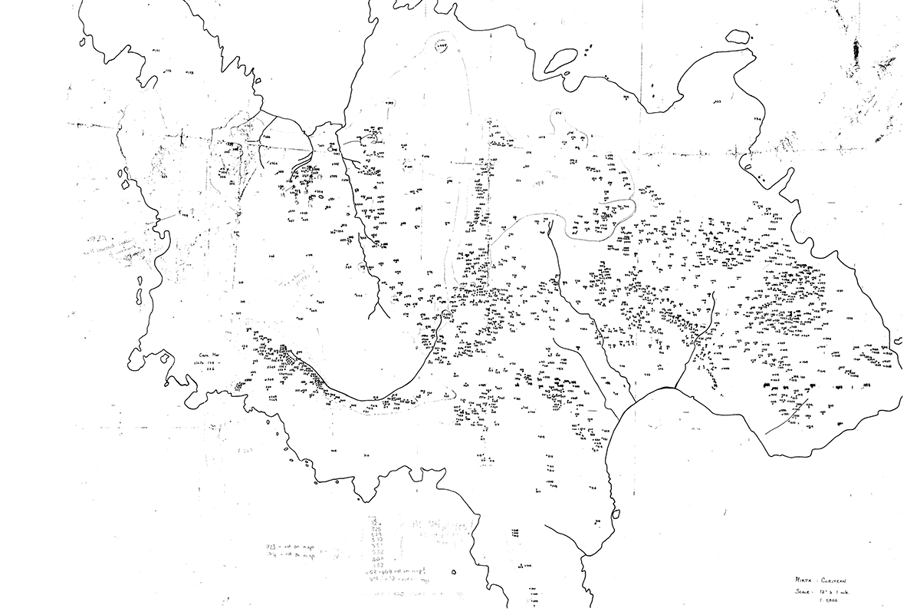

Dr Mary Harman (- present)

Through the research of archaeologist Dr Mary Harman, we have a detailed understanding remote St Kilda. The islands were inhabited until 1930 and are now one of Scotland’s world heritage sites.

Harman spent much of her childhood in different parts of Europe. She graduated in anthropology at University College London and visited the archipelago of St Kilda in the Outer Hebrides through the 1970s-80s.

She created the first detailed map of the islands, recording many of the structures for the first time. Her fieldwork centred on cleitean, stone structures of various sizes. Many of these can be found on Hirta, one of the biggest islands.

Her PhD from the School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh, is considered an encyclopaedia of St Kildan culture.

The Women of Scotland continued

Discover more of the unsung heroines and well-known women in Scotland's past.