The seas around Scotland are the most productive in the north-east Atlantic and entire communities have grown up around fishing. Seafarers first fished for food, then many began trading with each other before venturing overseas. Boatyards emerged and harbour industries developed to salt and smoke fish for sale.

Many coastal towns were transformed by the Fishery Board, which upgraded harbours to accommodate steam-trawlers. The busiest trading ports on the east coast had strong links with the continent while those on the west sailed to the Americas and Africa. In the 19th century, Scotland developed a world-famous reputation for heavy industry largely because of the shipbuilding carried out on the west coast and the engineering of magnificent bridges.

At the same time, resorts were developing around Scotland’s coast which had become a magnet for day trippers and holidaymakers, particularly in the west. The late 20th century oil boom transformed the north-east coast; now we look to the sea to help us generate wind, tidal and wave power.

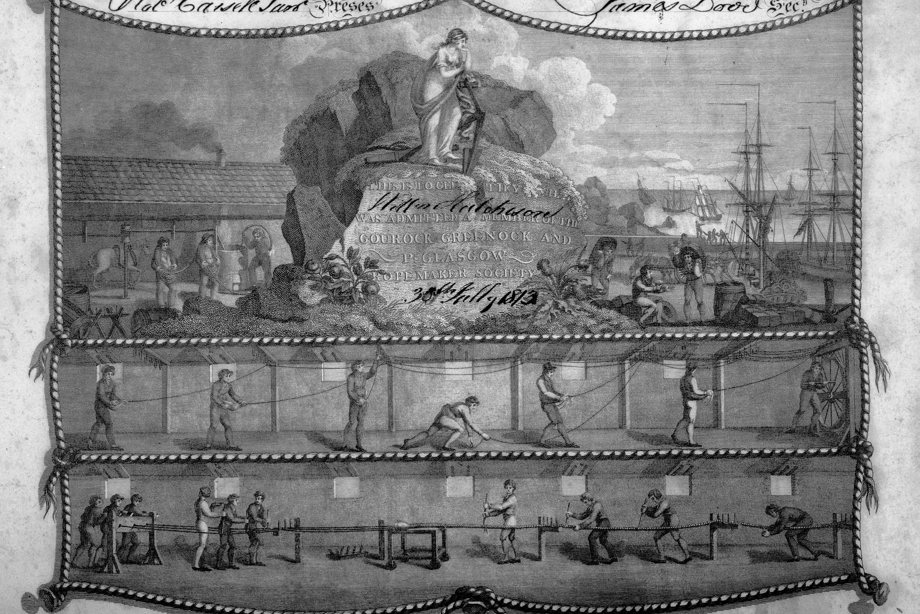

Greenock Ropeworks, 1813

Greenock became one of the busiest ports in Scotland in the 18th century.

Ocean-going trading ships could not navigate the shallow Clyde to Glasgow and so cargo had to be transferred here to smaller ships for the final part of the journey. Greenock therefore played a key role in importing goods such as sugar, cotton and tobacco, mostly produced using slave labour in the West Indies and southern states of North America.

As the port expanded, related industries such as the ropeworks were founded. Later, in addition to being a major point of departure for day trippers, Greenock was where travellers set sail on for New York and Canada.

Kirkcaldy Harbour, Fife, 1840

By the 19th century, Scotland’s long-established east-coast harbours had strong trading links with the continent.

This picturesque view shows Kirkcaldy’s bustling quayside with goods being loaded on and off sailing ships beside smaller fishing boats competing for space along the harbour wall.

The engraving was created in 1840, not long before a new dock was constructed to cope with an increasing volume of imports including the flax that would later be used in the town’s main industry, the manufacture of linoleum. The harbour was expanded again in 1906, largely to cope with the amount of linoleum being exported.

Leith Harbour, Edinburgh, 1818

In order that ports could expand to accommodate more ships, investment in their development was needed.

Alexander Nasmyth sketched the Shore area of Edinburgh’s Leith Harbour in 1818, the year after the completion of Scotland’s second wet dock, the first having been constructed on this site a few years earlier.

Wet docks held the water back in a harbour when the tide went out so that ships moored there could stay afloat and carry on loading and unloading cargo.

To make the point that he was drawing a Scottish scene, Nasmyth added a pair of sailors in tam o’shanter bonnets to the foreground.

Fishermen’s huts, Stenness, Shetland, c.1880

The enormous success of Scotland’s fishing industry in the 1880s relied on a seemingly endless supply of fish in the North Atlantic but the flexible way of life adopted by fisherfolk to maximise catches was also important.

The Shetland fishing station of Stenness was occupied for only a short time each summer.

The catch from 50 or so boats was dried on the shingle beach in front of the fishermen’s simple turf-roofed huts before being packed in barrels for transfer to market.

Peterhead Harbour, Aberdeenshire, c.1890

Fishing the bountiful supply of herring out of the North Sea led to an ever-increasing reliance on the ‘silver darlings’, as they were affectionately known, and the expansion of north-east harbour towns such as Peterhead.

Once the fish had been caught it had to be prepared before being sold.

The women and girls that were seasonally employed to gut the herring came mostly from the Hebrides. They would travel around the coast of Scotland in the summer preparing the fish and packing it with salt into barrels to preserve it.

Aberdeen fish market, Aberdeenshire, 1904

After steam trawling came to Aberdeen in 1882, catches expanded dramatically so that, in its heyday, Aberdeen was the second most successful fishing port in Britain after Grimsby.

This photograph from that time shows how the fishermen were able to unload their catch straight into the fish market for sale on the quayside.

The amount of fish being landed was manageable because the expansion of the railway network meant that catches could be delivered to markets much more quickly than had been possible in the past.

Despite the demands on the harbour infrastructure, modernisation did not begin until the 1960s.

Crail Harbour, Fife, 1885

The disappearance of the herring due to over-exploitation ended the fishing boom of the late 19th century.

Fishing communities therefore had to diversify to survive. Crail in the East Neuk of Fife supplemented what little fishing remained by trading in goods such as timber. The harbour was photographed in the process of adapting to this new way of life in the late 1880s.

The uncertain fortunes of smaller fishing villages such as Crail meant that many of their historic buildings survived with little alteration, something that now attracts tourists to areas like the East Neuk.

Forth Bridge under construction, City of Edinburgh, 1885

Scotland’s success in developing engineering during the 19th century was important in helping coastal areas to flourish.

Efficient transport underpinned the growing economy, and the masterpiece of engineering that is the Forth Bridge made a significant contribution to the prosperity of the country, so much so that it is now often thought of as a symbol of the nation.

4,600 workmen laboured to erect the first major structure in Britain to be built entirely from steel. These workmen were photographed with one of the 30 ton mooring blocks that secured the temporary floating structures needed when digging the foundation works on site.

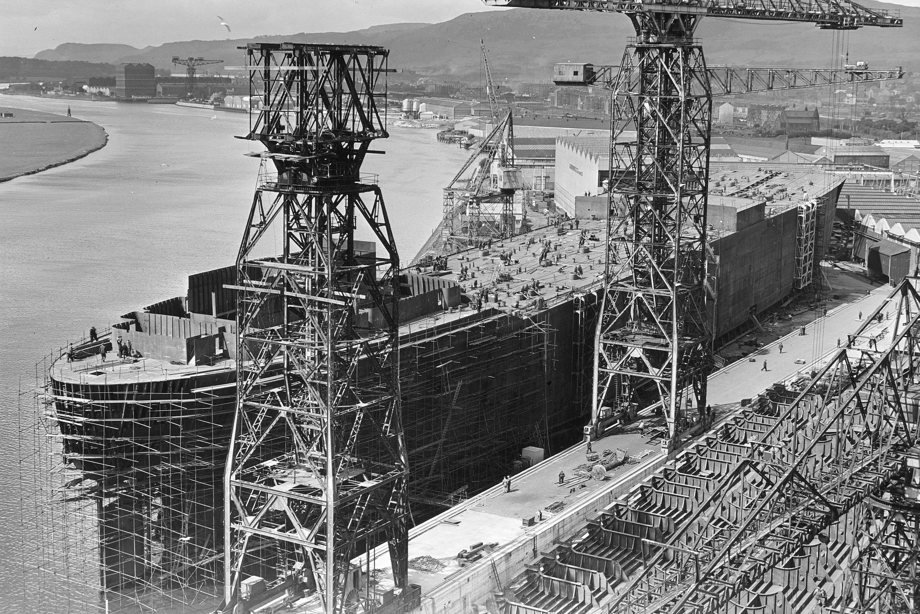

John Brown & Company Shipyard, West Dunbartonshire, 1959

Glasgow’s position on the west coast was a great advantage when trading with the Americas in the early 1700s.

Later, the River Clyde became one of the great industrial powerhouses of the world with shipbuilding replacing trading as the main activity on the river.

John Brown & Company specialised in iron-hulled passenger ships, the largest in the world being constructed here. The shipyard had to be reorganised so that one of these, the Lusitania, could be launched diagonally because it was wider than the Clyde. The river also had to be dredged so that the liner would not run aground due to its enormous weight.

Viking Cinema, Largs, 1938

During the 19th century, the leisure industry began to develop along the east and west coasts due to the popularity of steamer excursions. Local architect James Houston designed various buildings to serve the Ayrshire holiday trade.

A Viking theme was chosen for this cinema in reference to the Battle of Largs, during which the Scots defeated a group of Norwegian invaders in 1263.

The portcullis over the entrance could be lowered at night for security and the front half of a Viking ship built by a firm of Gourock boat builders sat in a pool of water to add to the effect.

Forth Road Bridge under construction, City of Edinburgh, 1962

As car ownership rose, Edinburgh needed to be connected to Fife by road as well as rail. It took ten years to plan the bridge, during which time an alternative solution involving a tunnel was also explored.

This view shows the bridge during the spinning of the cables from which the road surface was later suspended. A catwalk for workmen to use, before the platform was added, was constructed between the two towers and the land on either side; it can be seen directly below the cables.

When it opened in 1964, the new bridge was the longest steel suspension bridge in Europe.

Oil platforms, Cromarty Firth, Highland, 2016

The 1970s expansion of oil and gas extraction from under the North Sea led to a need for on-shore facilities, particularly in Shetland.

Repair and construction yards were also required, and the Cromarty Firth was an ideal location for these because, unusually for the east coast, it has deep, natural harbours.

By the time this photograph of the Invergordon Oil Rig Service Base was taken, less drilling was being carried out in the North Sea, which meant that fewer new rigs were needed. Instead work consisted of upgrading existing rigs temporarily moored in the Firth.

Scotland's Coast continued

Continue your exploration of Scotland's extraordinary coasts and waters.