Many people long to live by the sea, drawn by the beauty of its ever-changing moods and wide skies, but, for our ancestors, settling on the coast was a matter of survival. The seas were alive with fish and, once farming began, seaweed could be collected to fertilise the fields, and seawater evaporated in salt pans on the foreshore to produce salt for preserving and flavouring food. Over time, many settlements grew into thriving trading ports.

Later, as the seaside became associated with holidays, communities in popular resorts adapted to provide seasonal accommodation. But changing times have been challenging for coastal economies. As job opportunities in traditional industries have disappeared, many communities have shrunk as people leave to find work inland. Others have become commuter towns or home to the relocating self-employed. Now initiatives to regenerate coastal communities are encouraging more people to stay and work within their local area.

Nybster Broch, Caithness, Highland, 2002

Defence was a primary concern for Iron Age communities. The builders of Nybster Broch must have chosen this exposed site, surrounded by steep cliffs on three sides, for its natural strength.

The structure would have been accessible by land from only one direction and anyone approaching from the sea would have been easily spotted. Brochs are a special type of roundhouse found only in Scotland and occurring in great numbers throughout the Caithness landscape.

They are known to have been first constructed in the Scottish Iron Age and they were then occupied for several centuries.

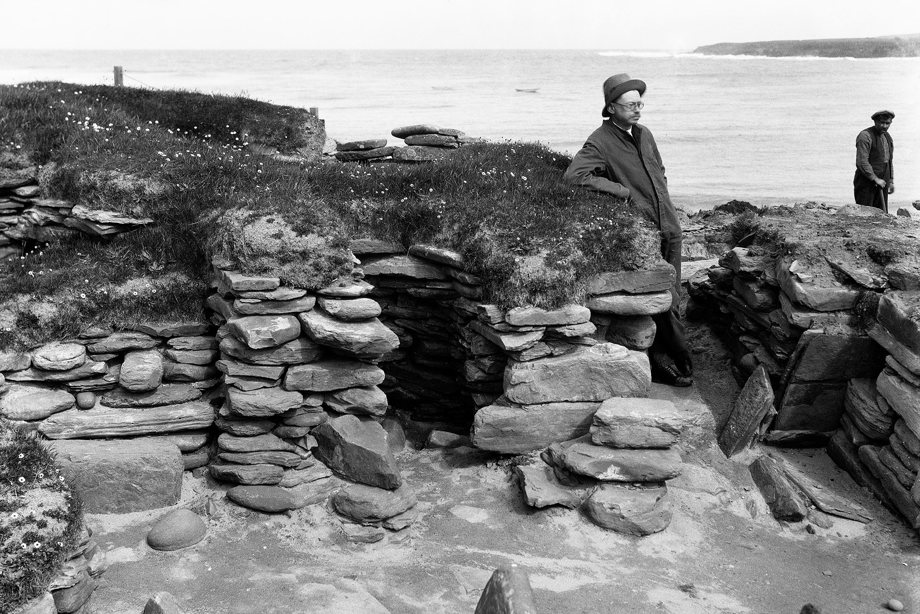

Skara Brae, Orkney, 1930

The oldest houses in north-west Europe are found on Orkney in a Neolithic settlement thought to be over 5,000 years old. Skara Brae is a well-preserved cluster of houses connected by paved passageways.

Partly underground, the drystone structures were insulated by being sunk into piles of midden left by previous settlers. Home comforts included stone bed recesses and cupboards with stone-lined hearths, while each house was provided with a drain that led into the village sewer.

Vere Gordon Childe, one of the best-known archaeologists of the 20th century, was photographed during his excavation of the site in 1930.

Viking occupation

By taking the most direct route across the Norwegian Sea from what is now Scandinavia, Viking raiders landed and settled first in the north-east of Scotland.

As a farmer living by the sea centuries later, John Nicolson was curious about what life might have been like for his ancestors. He drew this picture to illustrate what the Viking raiders could have looked like setting out to row to their longboat from the coastline near his home.

Nicolson worked alongside archaeologist Sir Francis Tress Barry on over 25 excavations and was highly regarded for his expert knowledge and enthusiasm.

Jarlshof, Shetland, 1973

Location has always been the key element in the founding of settlements. Despite its Viking name, Jarlshof on Shetland was first home to prehistoric inhabitants nearly 5,000 years ago; the site they chose was such a good one that it continued to be occupied for thousands of years.

When Viking settlers began arriving in their longships to raid Scotland in the late 700s they were so successful in their colonisation that within 50 years the Northern Isles had become thoroughly Norse.

Jarlshof was home to twelve generations of Scandinavian settlers and it is largely Viking buildings that we see there today.

Crovie, Aberdeenshire, 1962

For communities reliant on the sea, boats were a priority. Crovie was squeezed onto a strip of land at the bottom of a cliff because it lay beside a shingle beach; hauling boats out of the sea over pebbles was easier than over sand.

Being close to the water’s edge also meant that fish and equipment did not have to be carried far but it also exposed the village to the full force of the elements, so the cottages were built end-on to the sea.

Now that trawlers have transformed fishing, many of Crovie’s cottages have been converted into holiday homes.

Duff House, Aberdeenshire, 1797

Building has always been a way for the wealthy to demonstrate their success and Lord Braco was no different when he decided to build a house so enormous it would be visible from the sea.

Scotland’s leading architect, William Adam, designed Duff House in 1730 on an impressive scale intended to dominate the neighbouring town of Banff.

The extravagance of the project was too much even for a client as rich as Lord Braco: he never lived at the house, having fallen out with his architect over the cost, thereby leaving his descendants to finish the project.

Largs, North Ayrshire, 1923

As opportunities for work expanded in the 19th century, so did the desire of those working in urban environments to escape to the fresh air of the coast during their short holidays.

The expansion of the railway network transformed many places from the mid-19th century onwards including seaside towns such as Largs.

Living in a holiday hotspot created new opportunities, if only seasonally, whether for providing accommodation, refreshments or, as this view suggests, hiring out rowing boats.

Pollphail, Argyll and Bute, 2016

Much of Scotland’s coast is sparsely populated and so in order to develop coastal economies it has sometimes been necessary to provide workers with housing.

At Pollphail on Loch Fyne, the 1970s expansion of Scotland’s oil industry created an opportunity to construct a yard to build deep-water oil platforms. A housing complex for 500 workers was completed by 1977 but never occupied because plans for the yard were abandoned.

In 2009, the derelict buildings were transformed into a street art gallery by a group of artists called Agents of Change, who made a film about it called Ghost Village. Pollphail was demolished in 2016.

Port Murray, Maidans, 2009

Ever since the concept of having a holiday house has existed, the coast has been a popular place to rent or build one. Port Murray House on the Ayrshire coast was designed by Peter Womersley in 1961.

His modern, cantilevered design was constructed out of timber resting on a stone plinth and was awarded a Civic Trust Award in 1965. Unusually, the architect was given the clients’ E-type Jaguar car in place of his fees.

The building has been adapted over time, most surprisingly when an extension was added at the back for use as a carpet factory in the 1980s.

Dunbar fishermen’s houses, East Lothian, 1933–1952

Coastal economies can be vulnerable to decline because of their seasonal nature, which can lead to people moving away. In the 1930s, Dunbar Town Council began to regenerate the town’s harbour front by providing new houses for fishermen and their families, and to attract new families to the town.

It employed Basil Spence to design the houses in two phases using traditional materials in order to fit in with the surrounding buildings.

Construction finished in 1952, the year after Spence had become famous for winning the competition to design a cathedral for Coventry to replace the one that had been bombed during the Second World War.

Scotland's Coast continued

Continue your exploration of Scotland's extraordinary coasts and waters.