In the late 18th century, we began to be tourists in our own land. At first only the rich could travel for pleasure but gradually this became possible for many. The coming of the steamers transformed the west of Scotland into a tourist destination. During Glasgow Fair week in July the city emptied, and its workers swelled the population of seaside resorts several times over.

Going to the seaside became an established part of Victorian life. As well as the enjoyment of the sea and sands, sailing and golf were popular seaside pastimes. By the 1930s, resorts had fashionable modern lidos and dance-halls and were capitalising on the golden age of cinema with themed cinema buildings.

The tradition of a seaside break continued until budget package holidays began to lure holidaymakers overseas. We are now rediscovering the seaside for recreation as well as our wellbeing.

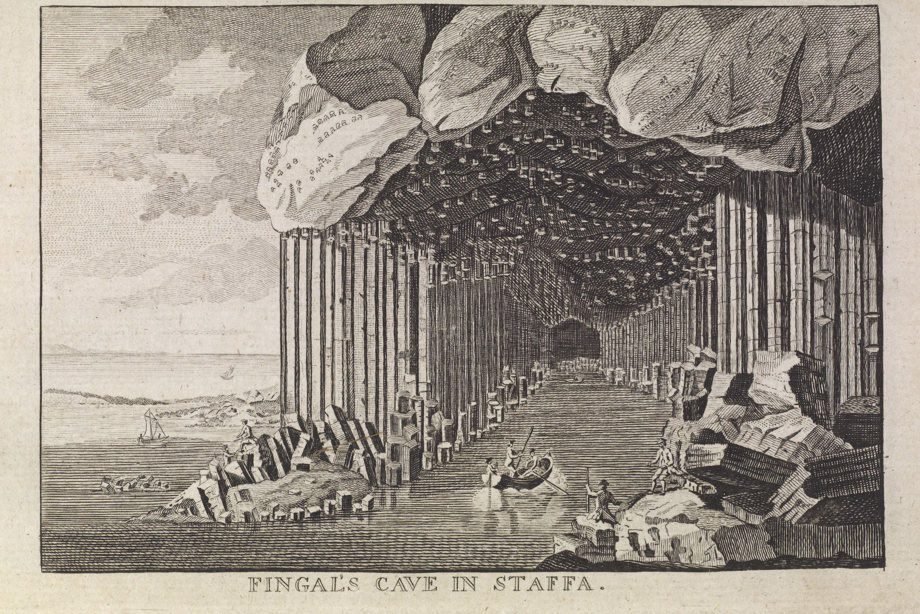

Fingal’s Cave, Staffa, Argyll and Bute, late 18th century

Early tourists were drawn to the coast by exciting accounts of travels around Scotland which began to be published in the late 1700s.

Newly published poetry, supposedly written by a Gaelic warrior named Ossian, also ignited the popular imagination, and the most intrepid admirers started braving the crossing to Staffa.

The combination of changeable weather and small boats meant that there was a risk of becoming stranded; one group had to shelter in the cave for three days until they could be rescued.

By the time Ossian had been revealed as a hoax, Fingal’s Cave was firmly established as a must-see tourist destination, still popular more than 200 years later.

Aberdour, Fife, c.1900

Aberdour has a natural harbour that dries out at low water, which made it of limited use to the boats serving local collieries in the 18th century.

However, the pretty village was an ideal place for a day trip, and visitors began arriving by Galloway steamer from Leith in the 1850s.

It became such a popular destination that a deeper water pier was built to better suit the steamers, which ran until the railway came to the village in 1890.

Portobello beach, City of Edinburgh, 1901

Sea bathing began to be popular in the 18th century as a medical treatment. By the time this photograph was taken, however, the main reason why so many took to the water was for a recreational ‘dook’ (dip).

The bathing huts wheeled down to the shoreline show that, on this day, the sea was appealing to swimmers, but there was also the luxurious option of indoor sea-water bathing at the newly built Portobello Public Baths.

Seen to the right of the image, the baths were intended to attract tourists with facilities that included Turkish baths, a gymnasium, reading room, smoking area and refreshment room.

Ayr beach, South Ayrshire, c.1905

Railways took Glasgow Fair day trippers ‘doon the water’ to resorts on the west coast, including Ayr, which was also popular with wealthier families who rented houses for the summer.

By this time cameras had become more portable and were easy enough for amateurs to use so people were increasingly taking photographs on their holidays and displaying them in albums.

Photographs could be taken more quickly than previously, with more spontaneous results such as this view of children joking with the photographer as they posed mid-paddle on a beach near Ayr.

Portobello Bathing Pool, City of Edinburgh, 1936

Seaside resorts had to maintain their popularity by providing new attractions. In 1936, an open-air swimming pool was built in Portobello that was designed to Olympic specifications and, in theory, heated with surplus water from a nearby power station.

The pool had a ballroom, restaurant and Scotland’s first electric wave-making machine, which produced 1-metre-high waves for 1,300 bathers. Entertainment for 6,000 spectators included floodlit evening galas and diving displays.

After the power station closed, the pool was no longer heated, and it fell into disuse. The revival in popularity of outdoor swimming came too late and the pool was demolished in 1989.

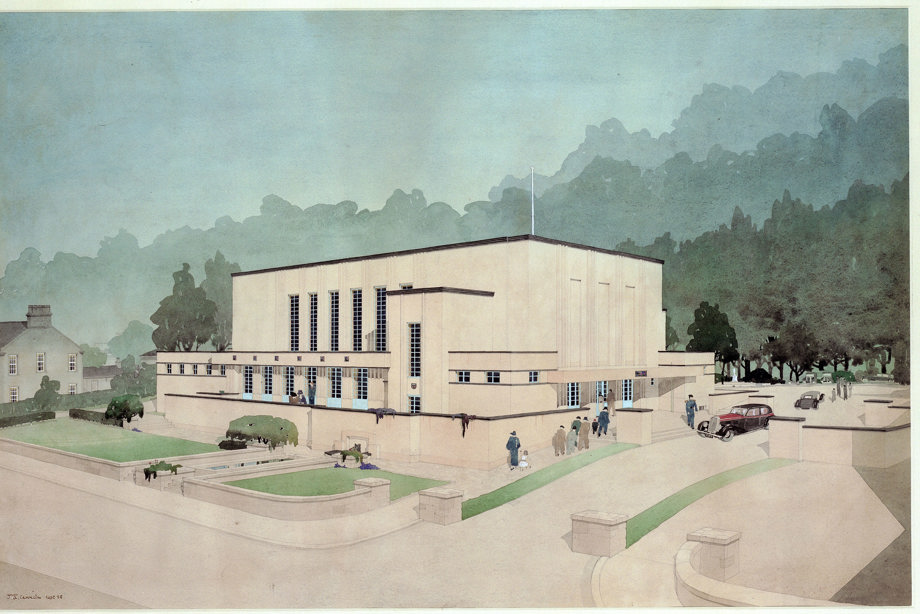

Cragburn Pavilion, Gourock, Inverclyde, 1935

The 1930s were a boom time for the leisure industry in Scotland. Seaside resorts responded by building leisure pavilions that could provide the entertainment which tourists now expected. In the west, many of the towns catering for holidaymakers built pavilions such as Dunoon, Prestwick, Gourock and Rothesay.

Architect James Carrick’s design for the Cragburn Pavilion was sleek and modern, with an auditorium for dance bands and a restaurant offering ‘the Glasgow holidaymaker an experience at the forefront of style in Scotland’.

Cragburn’s summer shows attracted many of Scotland’s top performing artists but by the 1990s the pavilion had become less used and was eventually demolished.

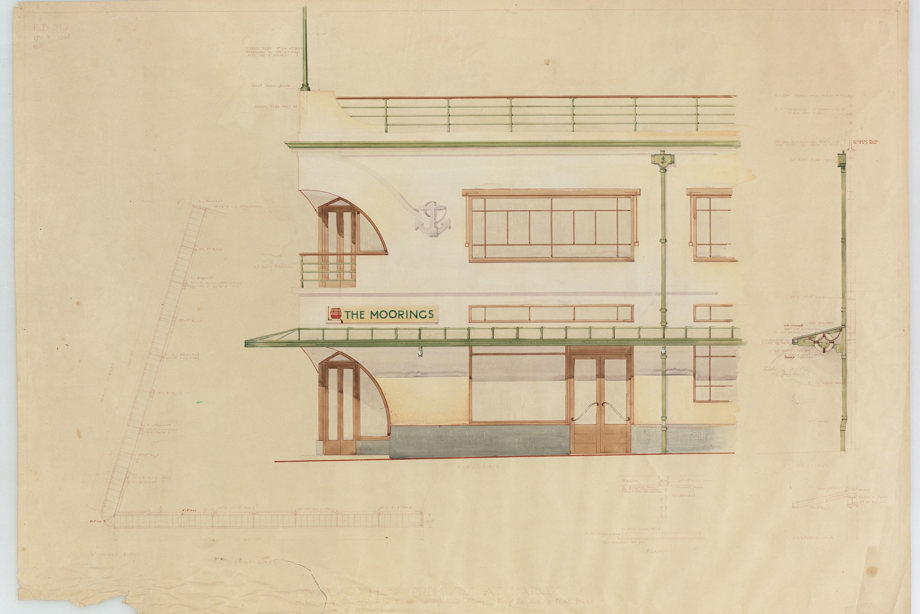

The Moorings, Largs, North Ayrshire, 1936

Largs was a popular port of call for steamers laden with factory workers escaping the smoky air of the city. Leo Castelvecchi commissioned premises on the seafront in Largs from James Houston, architect of the Viking Cinema (soon to be built nearby).

The building was designed to service the holiday trade and looked like a liner with a prow-shaped corner entrance, porthole windows and a railing along the top to suggest a sundeck.

It had its own café, ice-cream factory, bakery and a ballroom that could accommodate 1,000 people. The Moorings was demolished in 1989 and replaced with a new café building, the design of which reflects its predecessor.

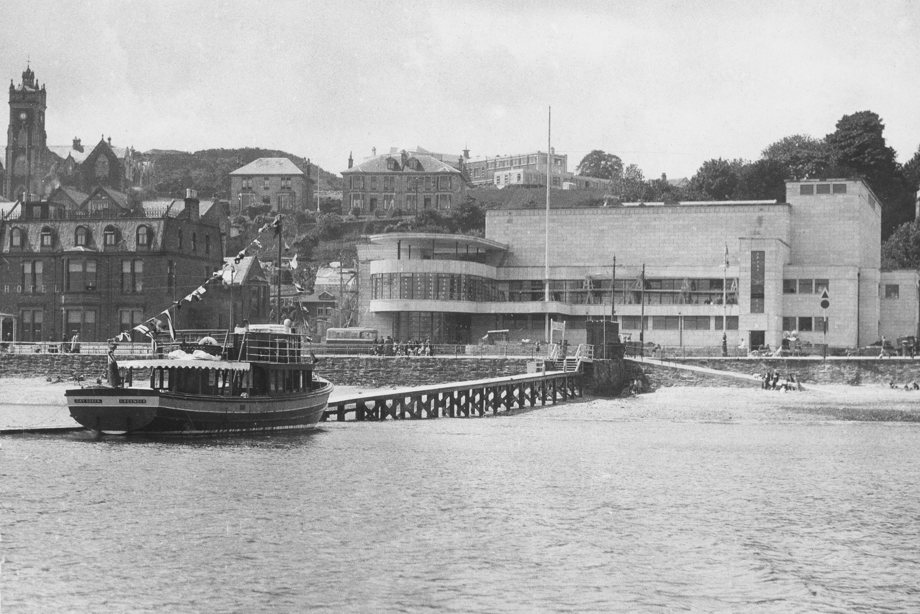

Rothesay Pavilion, Isle of Bute, Argyll and Bute, c.1938

As one of Scotland’s leading holiday resorts, Rothesay needed to make sure that it had up-to-the-minute tourist attractions. In 1872 it was the first place to create an esplanade.

It was also an early adopter of electric lighting for illuminating the evening promenade of the 50,000 visitors who made their way here each summer. The Rothesay Pavilion was the height of glamour when it opened on the seafront in 1938.

Designed by James Carrick, who had just finished building Gourock’s pavilion, it was a bold, modern statement and is Scotland’s best surviving example of its kind.

St Andrews Old Course, Fife, 2015

The possibility of combining a seaside holiday with a round of golf guaranteed the popularity of towns such as North Berwick and Troon and, most famously, St Andrews where the Old Course has been played since the early 15th century.

Golf has always been synonymous with Scotland, and for good reason. The Scots embraced the sport with uniquely democratic enthusiasm so that by the turn of the 20th century there were three times as many courses in Scotland as there were in England.

Scotland's Coast continued

Continue your exploration of Scotland's extraordinary coasts and waters.