Christianity was adopted gradually by the people of Scotland. At first it was incorporated into the pagan traditions of the Celts and Pictish tribes but, eventually, it almost entirely replaced them.

The transition from Pictish to Christian narratives is fascinatingly evident in the cross-slabs carved by the Picts. These combined Christian motifs along with symbols from the Picts own existing belief system, the meaning of which is now long lost.

St Ninian and, in the 6th century, Saint Columba, brought with them a radical new faith that required a fresh approach to building for spiritual gatherings. The new faith transformed the architecture of Scotland since Christianity brought with it artistic influences from the continent. These influences contributed significantly to the construction and decoration of Scotland’s churches, abbeys and monasteries. The foundations they established at Whithorn and Iona continue to be places of pilgrimage today.

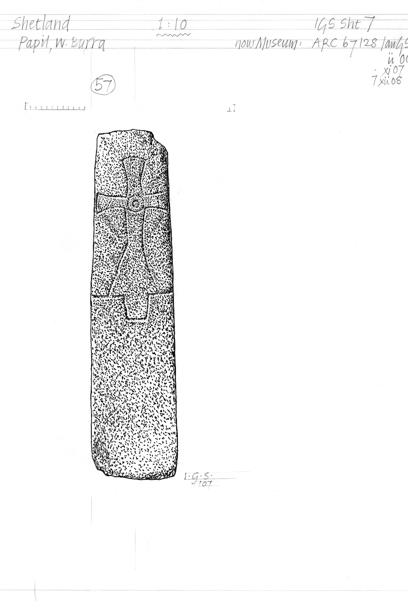

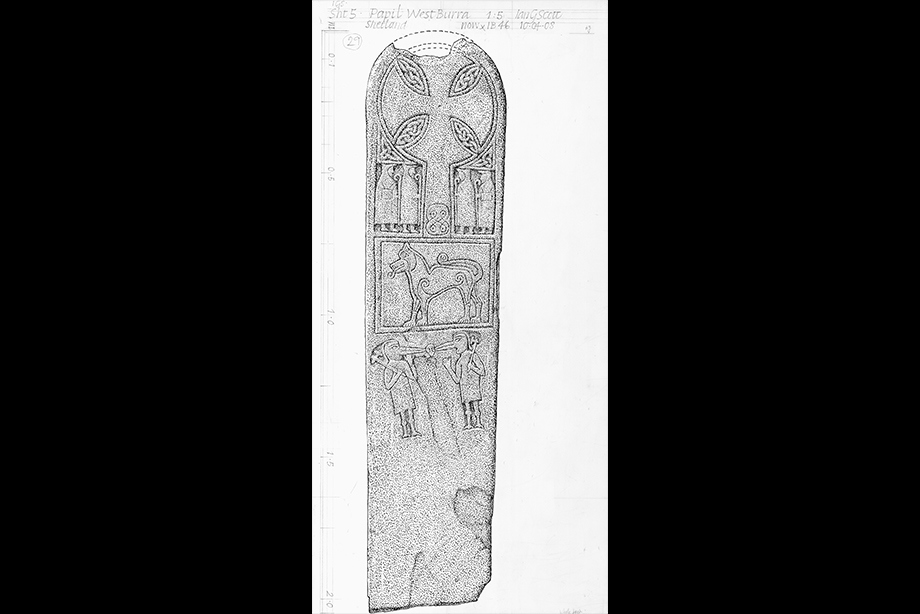

The Papil Stone, West Burra, Shetland

The Picts, and the hundreds of carved stones they created, continue to fascinate us because we know so little about them.

The Pictish tribes, who lived in the north and east of Scotland from around the 4th to 9th century AD, left no written records to explain the meanings of symbols they carved on these stones.

Having converted to Christianity from around the 6th century, they continued to carve stones, but combined Pictish symbols with Christian imagery or iconography.

This Pictish Papil Stone is a cross-slab and was used as a grave-marker in the churchyard of St Laurence Church in the Shetlands and stands on the site of several earlier churches. The date of the red sandstone monument is unknown, but it is thought to be from the 8th century.

The meaning of the mysterious figures with bird heads holding, or perhaps pecking at, a human head between their beaks, is long lost. Today, you can view (and come up with your interpretations about) this monumental grave slab at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.

Meigle Cross Slab, Perthshire

The mysterious Picts left an impressive legacy in the commemorative stones they carved over two centuries from the late 700s.

In the museum at Meigle, upon the site of a Pictish church, is a collection of 26 of these magnificent carved stone monuments. The largest and most opulently decorated of these is a cross-slab known as Meigle 2.

It is carved with a combination of Christian imagery, including a depiction of Daniel in the lions’ den, and Pictish designs such as hunting scenes.

This stone is traditionally said to have marked the grave of Vanora, better known as Queen Guinevere, the wife of King Arthur.

Iona Abbey, Iona, Argyll and Bute

Iona is arguably one of the most important Christian sites in Scotland. It came into being when a group of monks made the perilous trip from Ireland to the west of Scotland in the fifth century. It was St Columba, one of the most well-known of these early evangelists, who founded the monastic settlement on Iona in 563.

As the community grew, they produced illuminated (decorated) manuscripts and accumulated religious treasures made of precious metals. These proved irresistible to Viking raiders over the following centuries who murderously plundered the abbey four times until 878. Despite this, an active community remained at Iona and it continued to be a pilgrimage destination.

Although monastic life ended after the Reformation in the 16th century, the abbey wasn’t completely abandoned, and continued to be a place of some importance. It was only with the final abolition of bishops in the Church of Scotland that the abbey lost its previous influence.

Centuries later, the derelict abbey was rebuilt following the establishment of the Iona Cathedral Trust in 1899. It restored the nave, with work completed in 1910.

The Iona Community, an ecumenical Christian community, founded in 1938, restored the monastic living quarters, finishing in the 1960s. The abbey continues to be a place of Christian pilgrimage to this day.

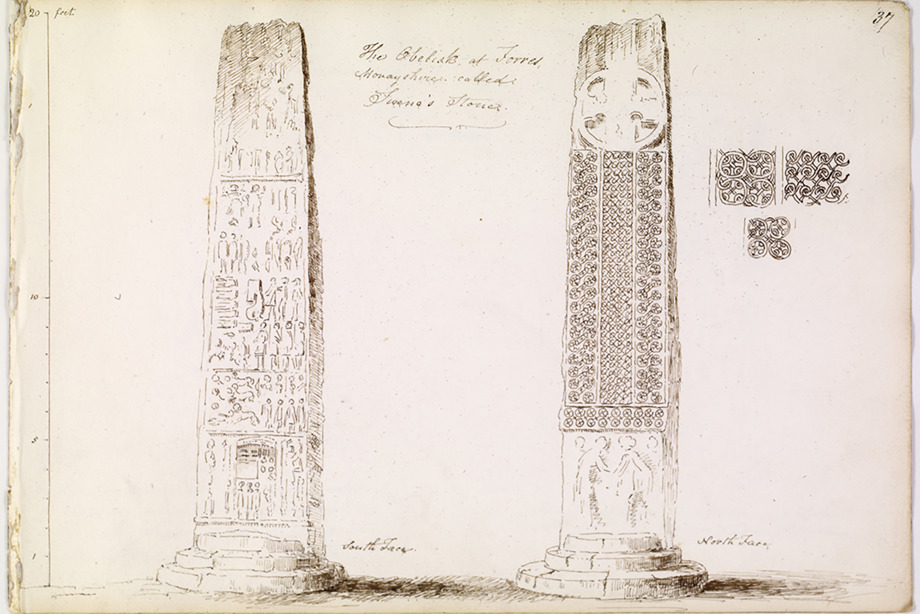

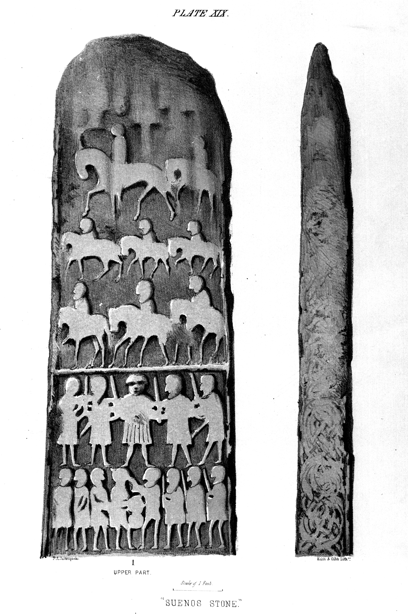

Sueno’s Stone, Forres, Moray

Sueno’s Stone is the tallest and most extravagantly carved piece of early medieval sculpture in Scotland. It was most likely carved between 850-950AD by the Picts who lived in the north and east of Scotland at the time.

One side of the stone depicts a gruesome battle scene with nearly 100 figures, many of them decapitated bodies, flanked by piles of heads.

The other side of the sculpture is dominated by a tall, carved cross showing their adoption of Christian beliefs. The carved cross also suggests that this site was a place where people came to pray, perhaps in gratitude for victory in the battle it records, or to remember a patron now long forgotten.

Carved stones were often moved from their original settings, either to use as building materials or to be displayed in museums, but Sueno’s Stone probably remains where it was first erected. Where possible, carved stones are now left where they are found although - in order to protect them from deterioration - they are sometimes covered up during the winter or, as is the case with Sueno’s Stone, with a permanent enclosure..

Sueno Stone

Explore this stone carved stone more closely with this 3D scanned model.

Dalmeny Parish Church, Dalmeny, City of Edinburgh

Dalmeny Church is the most complete Romanesque church to survive in Scotland.

As with many churches, however, it has been altered over the centuries to suit the changing needs of its congregation, including the addition of an aisle by the Earl of Rosebery for his family in 1671.

It features a magnificent zigzag decorative archway dating to the 12th century and there are many visible masons' marks on the stonework inside the church. This was done to record which stones each stonemason worked on and, therefore, how much they should be paid.

In the case of Dalmeny Church, the marks show that the same masons worked at Dunfermline Abbey and Leuchars Church across the water in Fife.

Govan Old Parish Church, Glasgow

Many of Scotland’s churches became important places of pilgrimage. To accommodate the numerous pilgrims and the needs of the religious community, churches were often rebuilt and expanded several times on the same site.

Known locally as ‘the people’s cathedral’, this 19th century church in Govan was built on the foundations of one of the oldest sites of Christian worship in Glasgow.

31 Early Christian carved stones, now housed inside the church, provide us with one of the largest groups of intact early medieval sculpture in Scotland.

Dating from the 10th century, it includes five grave markers known latterly as ‘hogbacks’ due to their animal-like shape. The decoration on the stones varies; many are carved and have a design along the sides that represents roof shingles.

This style of commemorative stone was introduced to Scotland by Norse settlers. Research has since shown us that the shape of the stones echo house structures found in Scandinavia at the time, suggesting that their form represents homes for the dead.

Hogback stone, Inchcolm Abbey

Dating to around the 10th century, this early medieval grave marker was discovered near Incholm Abbey.

St Margaret’s Chapel, Edinburgh Castle

Castle Rock, upon which Edinburgh Castle sits, has been a site of immense importance for millennia with the earliest evidence for human settlement dating to around 900 BC.

This site has been continuously inhabited ever since and has witnessed some of the most significant moments in Scottish history.

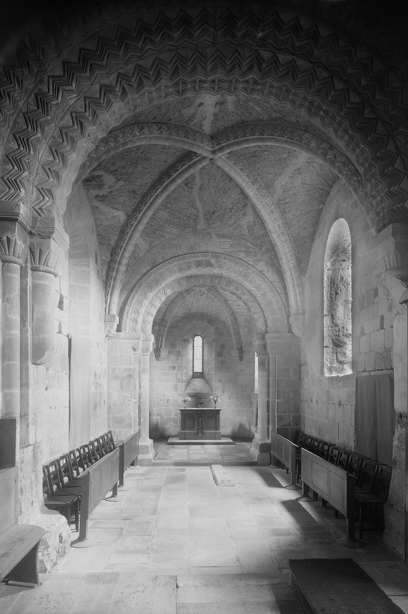

St Margaret's Chapel lies within the castle complex. This unassuming little structure was built in the early 12th century by King David I who dedicated it to his devout Christian mother, Queen Margaret. Not only is the chapel the oldest building within the castle, but it is also the oldest surviving building in the city of Edinburgh itself.

Queen Margaret was renowned for her charitable works; one such example is her provision of a ferry across the Firth of Forth (the crossing points later named North and South Queensferry in her memory) in order that pilgrims could travel more easily to St Andrews. For this, and many other acts of Christian charity, she was declared a saint by the Pope in 1249.

St Margaret’s Chapel is a rare example of a place of prayer that was adapted for a non-religious purpose but was later reinstated as a worship space. It had been used as an ammunition store for three hundred years until 1845 but when the building’s original purpose was rediscovered, work began on its restoration as a chapel.

In 1934 it was rededicated and, not long after, St Margaret’s Chapel Guild was set up to place flowers in the chapel every week. It continues to take care for it today in partnership with Historic Environment Scotland.

Places for Prayer continued

Explore the magnificent cathedrals and abbeys that dominated Scotland's landscape and attracted pilgrims to pray