Throughout history, many sacred spaces where people worship have attracted those with the greatest artistic or design skills of their day.

A common striving to produce the very best is what links creators of prehistoric stone circles, medieval stained-glass artists, and 21st century painters of gurdwara interiors.

While this may have represented an expression of faith on the part of the craftspeople and their patrons, it also presented opportunities for those who wished to demonstrate their wealth and status.

Either way, the imagery and symbolism expressed through the artistry not only celebrates but illustrates religious ideas and stories in an accessible way.

Architecture

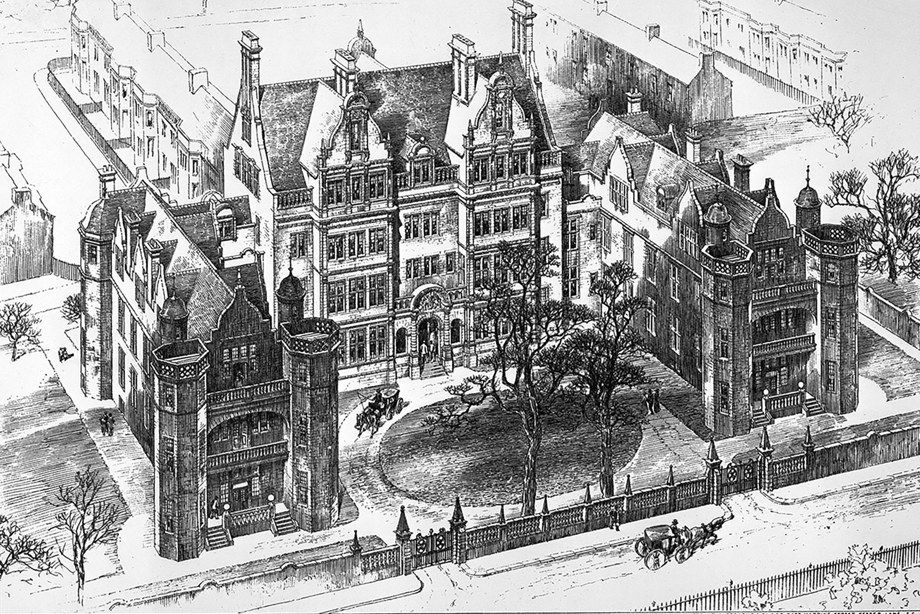

Garnethill Synagogue, Glasgow

Records of Jewish people in Scotland can be traced back to the 17th century, but it was not until 1823 that the Glasgow Hebrew Congregation was officially formed. It took another 65 years for Scotland’s first purpose-built synagogue to be built in Garnethill which opened in 1879.

The local architect of this impressive building, John McLeod, had previously designed churches but was unfamiliar with what architectural features must be considered when designing a synagogue. Therefore, he worked in conjunction with London architect Nathan Solomon Joseph, who had designed a synagogue for Belfast a few years earlier.

The synagogue is orthodox, so women sit upstairs in the gallery and take no active part in the service.

As well as being a place of worship, the building houses the Scottish Jewish Archives Centre.

Hindu Mandir, Glasgow

The Hindu Mandir, or temple, occupies what was once the Queen’s Rooms, a 19th century concert hall.

From 1912 it was occupied by the First Church of Christ, Scientist and, in the early 1990s, it was adapted again to become Scotland’s first Hindu Mandir.

Many original features from the concert hall remain, such as the stepped seating where worshippers now sit on the carpeted floor, and the arch around the central altar. The religious elements, from the deities to the altar structures, have all come from India.

The altar area houses the most important deities including Krishna and Radha in the centre, Shivlinga to the left and Goddess Durga to the right.

Painted decoration

Mortuary Chapel, Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh

The choice of artist is critical when considering sacred and prayerful places. Even more so when the space has been specifically designed as a sanctuary for those in need of comfort or reassurance during times of intense suffering.

Artist Phoebe Traquair decorated the Mortuary Chapel at Edinburgh’s Hospital for Sick Children in 1885 with a beautiful series of murals. These were thoughtfully designed to be appropriate for their sad purpose.

The walls and ceiling are covered with emotive images: child size angels with their arms outstretched to offer comfort to those praying in the hope of resurrection and the prospect of meeting their loved ones again. When a new hospital was constructed ten years later, a public campaign ensured the reinstatement of these murals in the new building.

This was Traquair’s first commission and she went on to become the first woman in Scotland to achieve great commercial success as a professional artist.

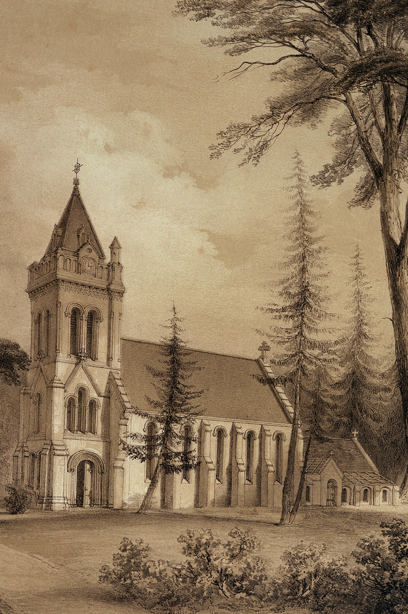

Chapel of St Anthony the Eremite, Murthly

While churches were often dedicated to individuals - such as saints or Mary, the mother of Christ - they were sometimes built to commemorate specific events too. For instance, Sir William Drummond Stewart, the patron of the Chapel of St Anthony, wanted to celebrate the fact that he had converted to Catholicism.

In 1845, he commissioned the construction of the first Catholic church in Scotland since the Reformation of the early 16th century. He chose two of the finest architects of the day, James Gillespie Graham and A.W.N Pugin to undertake his ambitious commission.

Above the gilded and marble columned nave (the main body of a church that holds the congregation), the ceiling forms a heavenly canopy of blue studded with gold stars. Sir William, thus, marked his conversion in an exuberantly decorative and demonstrative way.

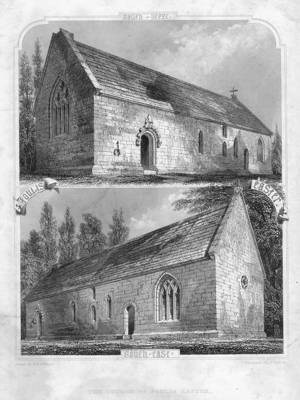

Some churches may seem quite plain from the outside but, once entered, they are revealed to be hidden gems with highly decorated interiors. One such church is Fowlis Easter, which was built in 1453 and has a deceptively simple exterior.

Lord Grey, who paid for its construction as a collegiate church, chose to focus his efforts on decorating the interior. A series of painted wooden panels at the east end of the church are covered with lively Biblical scenes.

Teeming with figures dressed in 15th century costume, the panels would have brought a contemporary relatability to the depiction of Jesus being crucified. At the time of the Reformation, when church interiors were being stripped of what was considered unsuitable decoration, the panels were hidden from view.

In 1889, the church interior was reorganised and the painted panels were discovered and put on display once again.

St Salvador’s Episcopal Church, Dundee

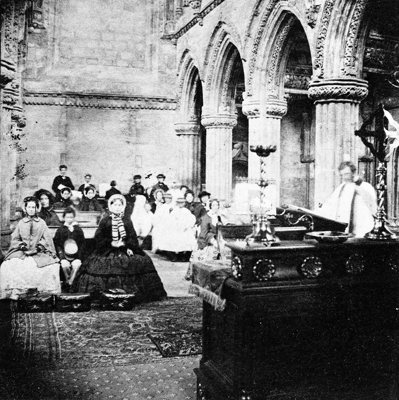

Dundee’s rapid industrial expansion in the 19th century led to such an influx of workers that many ended up living in overcrowded squalor.

Bishop Alexander Forbes’ mission - to improve the lives of those in the city’s Hilltown - began with the building of a school and the education of the children living in the area.

This was followed in 1878 by the construction of the church itself, which was intended to be spiritual support for the community and a hopeful reminder of the glories awaiting in heaven.

The architect, G F Bodley, considered the church as a ‘jewel casket’ as every surface is either stencilled or brightly painted. The use of shimmering gold on the east wall behind the altar emphasises the most important part of the building where the Eucharistic liturgy is celebrated.

Stained glass

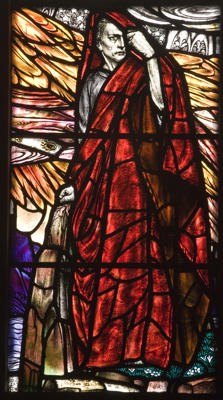

Lowson Memorial Church, Forfar, Angus

Since medieval times, stained glass has been used to flood the interiors of holy spaces with light and colour. The scenes depicted on the stained glass helped explain the Christian message to all believers over the centuries, regardless of their ability to read.

Although stained glass windows are costly to produce, they are often donated in memory of individuals or events. Lowson Memorial Church was named after John Lowson, a local linen manufacturer whose bequest helped build a new church in Forfar in 1914. Douglas Strachan, Scotland’s leading stained-glass artist, was commissioned to create a magnificent window based on the story of creation.

Inspired by the medieval stained glass he had seen in different European countries, Strachan designed a scheme that was contemporary while respecting the Gothic architectural style of the church. His figures stand along the bottom of the window in a traditional way while above them, the seven days of creation are pictured within a vast, divine circle.

Wood carving

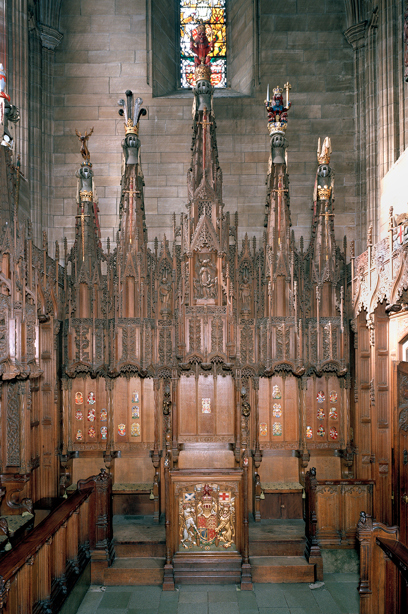

Thistle Chapel, St Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh

Some of the most expressive, decorative elements in a church are often those carved in wood. The woodwork in the Thistle Chapel is a particularly magnificent example of skill and expression. For example, the form of an elaborately carved casket which was added to St Giles Cathedral in 1911 for ceremonial use by the Knights of the Order of the Thistle.

Each Knight was given their own stall topped with their heraldic crest. Highly skilled craftsmen, such as woodcarver brothers William and Alexander Clow, were chosen by the architect Robert Lorimer to realise his vision.

The woodwork is a crucial element of Lorimer’s design, with the naturalistic forms of animals and plants echoing the Gothic roots of the cathedral.

Church furnishings

The furnishings (fixtures and fittings) of Christian churches were often mass produced but, when funds allowed, they could be custom designed.

At the turn of the 20th century, the leading supplier of church woodwork was Edinburgh-based Scott Morton and Company. We don’t know which Church of Scotland building this unusually elaborate set of furniture was designed for, but it may have been commissioned as a gift. It comprises of a communion table, a seat for the minister and pair of chairs for the elders.

Replacing church furniture was often carried out at the bequest of a member of the congregation. This was sometimes driven by functional reasons – for example when a congregation had expanded, and new seating was needed – but it was also done to improve the comfort or look of the interior. Pews could be either added in or taken out, and lecterns, pulpits and fonts could be upgraded with more contemporary designs.

With so many churches now being converted for alternative (secular) uses, a great deal of church furniture is being sold on the open market.

St Paul’s RC Church, Glenrothes

Modern churches, built in a contemporary style after World War II, were generally furnished in an equally modern fashion. The Roman Catholic church of St Paul’s was an essential addition to the New Town of Glenrothes because the area was intended to house a largely Catholic community of miners who were being relocated from the west of Scotland.

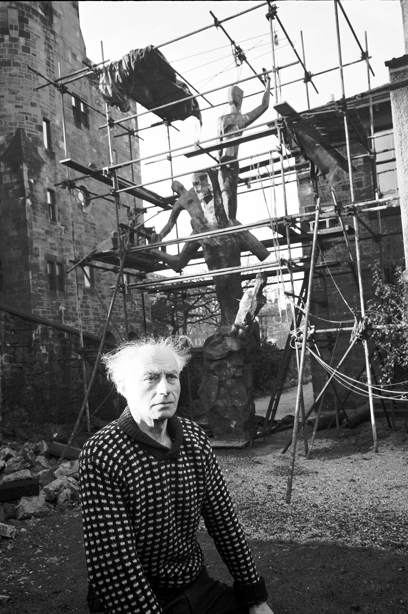

St Paul’s, which opened in 1958, was the first of Gillespie, Kidd and Coia’s experimentally modern church designs. To complement its minimalist, white painted interior, the sculptor Benno Schotz – Head of Sculpture at Glasgow School of Art – was chosen to design a monumental 12-foot high metal cross for the main altar, and a Madonna, or Mary, the mother of Christ, for the Lady Chapel.

Needlework

Needlework adds decorative colour and texture to many sacred spaces. The patterns or images created are often full of significance and tell a story beyond what we can simply see.

Church embroidery was largely the domain of women and, since the arrival of Christianity in Scotland until the 20th century, it was one of the few ways in which they could visibly contribute to what was a male-dominated environment.

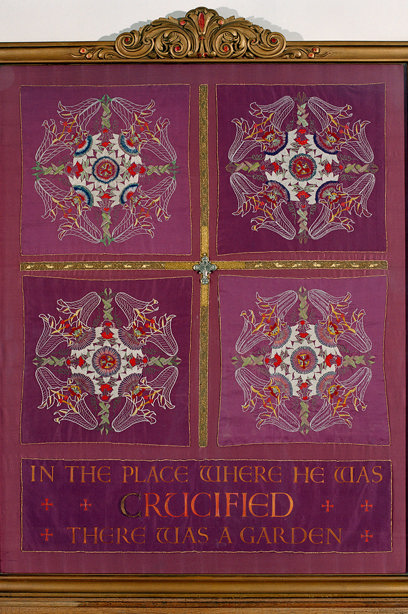

Kippen Parish Church, Stirling

From the earliest days of Christianity, the robes and vestments worn by the clergy – specifically priests who led the Eucharistic services - were embroidered with ornate designs. This highly skilled, painstakingly detailed task was often carried out by nuns as well as by aristocratic women of leisure.

As time went on, women from all parts of society began to produce needlework for their own places of worship, particularly kneelers to help make the long periods of kneeling during services more comfortable.

Needlework was, in a way, an opportunity for women to make their contributions to their local parish church visible. They did this by replacing the altar frontals for particular festivals - such as this altar cloth made for the Easter period at Kippen Parish Church – and it was also an opportunity to bring contemporary design into historic church interiors.

Sculpture

Rosslyn Chapel, Midlothian

Churches have been traditionally built from stone since the 12th century when available building materials, skills and resources allowed.

These important buildings were intended to last for centuries and to be recognisable as places of Christian worship. One way of doing this was by decorating them with carved stone.

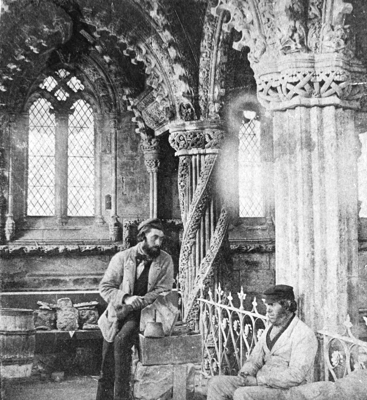

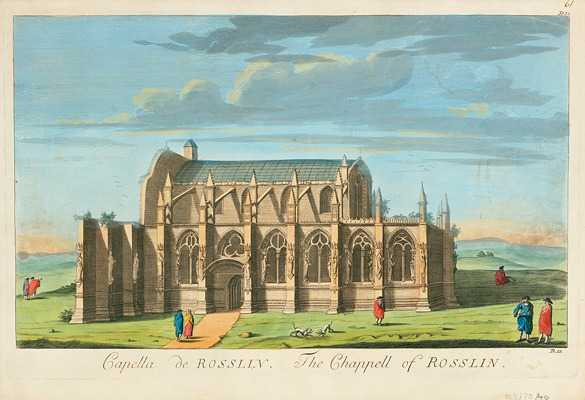

Built around 1446, Rosslyn (also known as Roslin) Chapel is an exceptionally ornate example of the stone-carver’s skill; it seems that every surface is covered with animals, plants and human figures.

Winged serpents curl around the base of columns and there are representations of the Seven Deadly Sins and Seven Virtuous Acts for the congregation to reflect upon.

Given the expensive complexity of the decoration, it is perhaps unsurprising that the church was never completed; despite its scale, what we see today is only the choir of the much bigger church that was originally planned.

The mason pillar, Rosslyn Chapel

This is the Mason’s Pillar, accredited to the work of the master mason, situated in front of the Lady Chapel at Rosslyn Chapel.

Rosslyn Chapel in 3D

This 3D record of Rosslyn Chapel captures the architecture down to the millimetre.

St Clement’s Church, Rodel, Harris

In many religions, sacred spaces include an important and specific function: the memorialisation of the dead. In this example, we see some remarkable, early funerary monuments that survived at St Clement’s Church.

Dating from the 1520s, a group of wall tombs include some of the most richly carved stonework of the time in Scotland. Alexander Macleod, 8th chief of the clan Macleod, made sure to prepare his own burial place before he died.

Decades later he was laid to rest in his elaborate tomb which is bordered with carved stone panels. In addition to biblical scenes, he chose to illustrate the status of the MacLeod clan and the earthly attributes of a Gaelic lord through stone carving.

In particular, the key aspects of his life that he wished to be remembered for were the clan stronghold, Dunvegan Castle on Skye, his nautical prowess and the fact that he enjoyed stag hunting, a pastime long associated with royalty.

Queensberry Monument, Durisdeer Parish Church

Sometimes a tomb can be far grander than the church in which it lies. Wealthy patrons, who wanted to commemorate their loved ones close to home, sometimes had no choice other than to install an ornate funerary monument in what was a very simple, local church.

Durisdeer Parish Church, located in Dumfries and Galloway, is an elegantly plain building which gives no outwardly hint of the spectacular, baroque monument contained inside.

The Douglas family added a burial aisle onto the side of the church to celebrate having been awarded the title, Duke of Queensberry. Then, around 1710, sculptor Jan van Nost carved a magnificent marble memorial to the 2nd Duke and his wife.

Dressed in realistically draped finery, the couple sleep beneath a free-standing baldacchino - a canopy supported on four barley-sugar columns - which was designed by James Smith, architect of the church.

Places for Prayer continued

Some places for prayer in Scotland are now playing new or adapted roles in their communities, while maintaining the cultural and architectural features that make them so special. Explore the present (and future) of these exceptional sites.