The wealth of prehistoric monuments found in Scotland tells us that, for thousands of years, people have created special places for activities beyond what is needed for basic survival.

We can’t know for certain what these ancient communities who lived in Scotland, as we now know it, believed, because their legacy was passed on through oral tradition rather than by written records. However, we can be confident that many places held immense meaning for them.

The ingenuity and resources needed to build sites that we see today – such as stone and timber circles, earthworks and burial chambers – show us that ritual was of great importance. Archaeologists have found evidence to suggest that feasting, lighting fires, and burying funerary remains were carried out at these places.

The natural world appears to have been central to the spiritual life of the early inhabitants of Scotland. This was recognised by the Christian Church that followed with healing wells being adopted as Holy Wells and churches built beside stone circles.

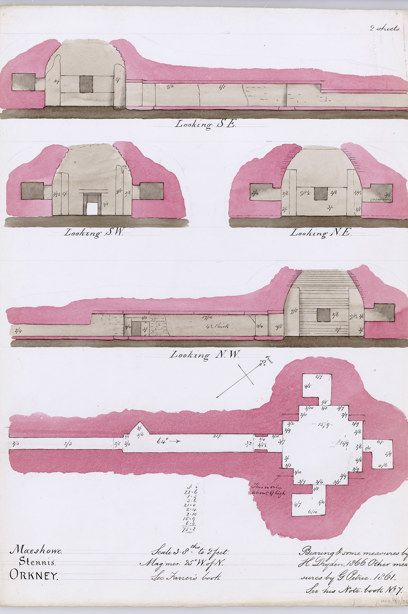

Maeshowe Chambered Cairn, Orkney

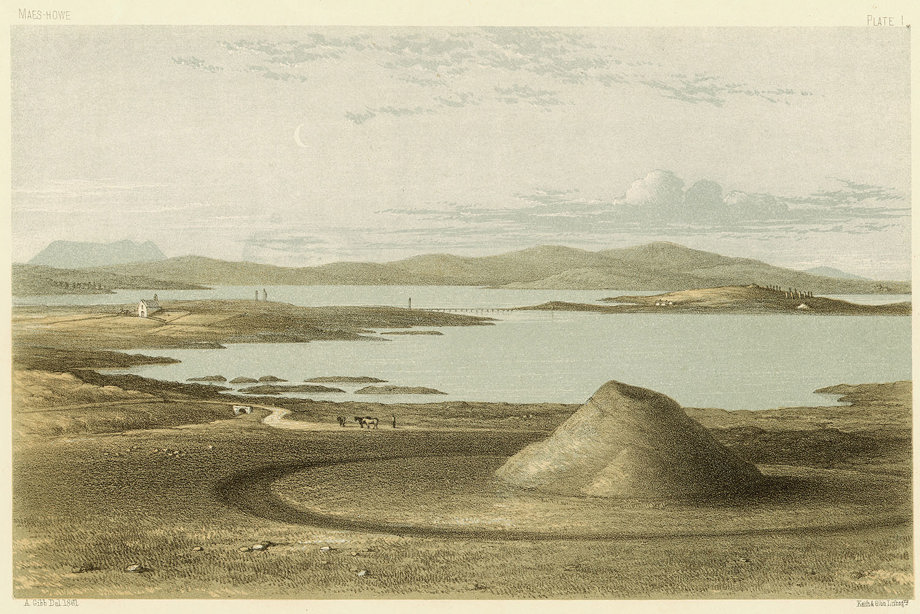

Maeshowe, a monumental chambered tomb, is one of the finest Neolithic structures to survive in north-west Europe. It shows us how important it was for ancient peoples to have a place to commemorate their dead.

Maeshowe sits within a highly complex archaeological landscape in Orkney which includes other sites such as Skara Brae, the Ring of Brodgar, and the Stones of Stenness. These give us a fascinating insight into the domestic, ceremonial and burial practices of Neolithic culture.

Built around 2700 BC (nearly 5,000 years ago) using gigantic stone slabs, smaller stones, and earth, this chambered cairn is a masterpiece of design and construction. A long, low passageway leads to an inner chamber with smaller cells on three sides. Sun from the winter solstice catches the light here today as it did when it was constructed. From the outside, Maeshowe looks like a large grassy mound, which explains the use of the ‘howe’ in ‘Maeshowe’ as that comes from the Old Norse for ‘hill’.

Although we don’t know if Maeshowe was constructed just to house the remains of ancestors or if there were more ritualistic intentions, we can tell that the site must have meant a great deal to those who built it as it required a high level of skill, observation, co-operation and planning.

Download our 'Explore Maeshowe' app to explore the interior and exterior of the tomb with complete 360° views all from the comfort of your home.

Stones of Stenness, Orkney

These four enormous monoliths are all that remain of what may be the oldest henge monument in the British Isles. A henge is a prehistoric circular or oval earthen enclosure, some with a stone or timber circle within the outer ditch. This one dates from around 5,000 years ago, during the Neolithic Age.

There were possibly twelve stones in total, but evidence suggests the circle was never completed, so there may have been more. Manually erecting the colossal stones was an incredible feat of human ingenuity and ability. The tallest stone we can see standing today is over five metres high, so moving this must have required a significant number of people and organisation.

At Stenness the henge is broken on the northern side by an entrance causeway which would have allowed access to the stones within. Today, the henge is not as visible as it once was due to centuries of ploughing.

Archaeologists discovered a hearth at the centre of the stone circle, typical of those found within Neolithic dwellings such as the nearby Barnhouse or Skara Brae. Built from four stone slabs, the hearth contained traces of bone, charcoal and pottery suggesting that activities such as feasting were carried out here.

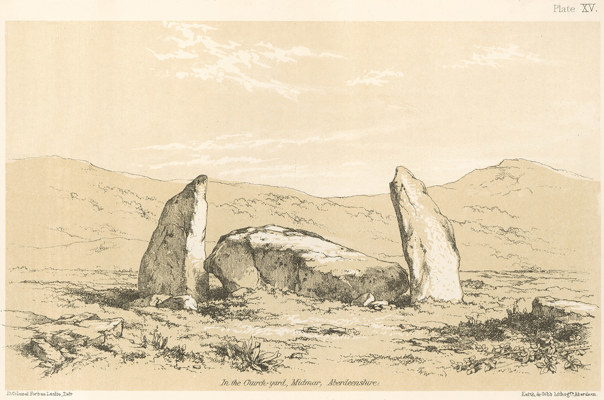

Recumbent stone circle, Midmar Parish Kirk, Aberdeenshire

Although constructed thousands of years apart, the proximity of Midmar Parish Kirk to the stone circle incorporated into its kirkyard, shows us that this place has been layered with belief, practices, and ritual from the Bronze Age to the present day.

The 18th century kirk was deliberately built close to the circle because, at the time, it was believed that the stone circle was a Druidical structure. Druids were thought to have worshipped a single god and this apparent sharing of a fundamental belief with the Judeo-Christian religion made it seem appropriate to build a church so close to the stone circle. Nevertheless, we cannot know for certain what the Druids believed because they left no written records.

The circle is described as ‘recumbent’ because one of its huge stones has been placed horizontally. While it may have been that this was intentional, so that its surface could be used during some sort of ritual, there is no proof that this was the case. Although, in the past, the recumbent stone was likened to an altar in a Christian church, it is now thought to have been a symbolic doorway.

Ritual Enclosure, Struidh, Eigg

Little is known about religious practices in western Scotland during the Iron Age (c.700 BC – AD 500) but, on the Isle of Eigg, archaeologists identified a site which may have been used as a sacred place.

At the foot of the dramatic cliffs of Sron na h-Iolaire, a stone platform was created around a small circular stone building which concealed the entrance to an underground chamber running beneath a field of boulders.

Looking towards the cliffs from the remains of the circular structure, there is a sense that this was a special place for the inhabitants of the island as they framed the view with a pair of giant boulders.

Considering the placement of the circular building, its inaccessible location and the resource required to build it, it is unlikely that this structure would have just been a domestic residence. In fact, archaeologists believe that prehistoric ritual practices may have been carried out here.

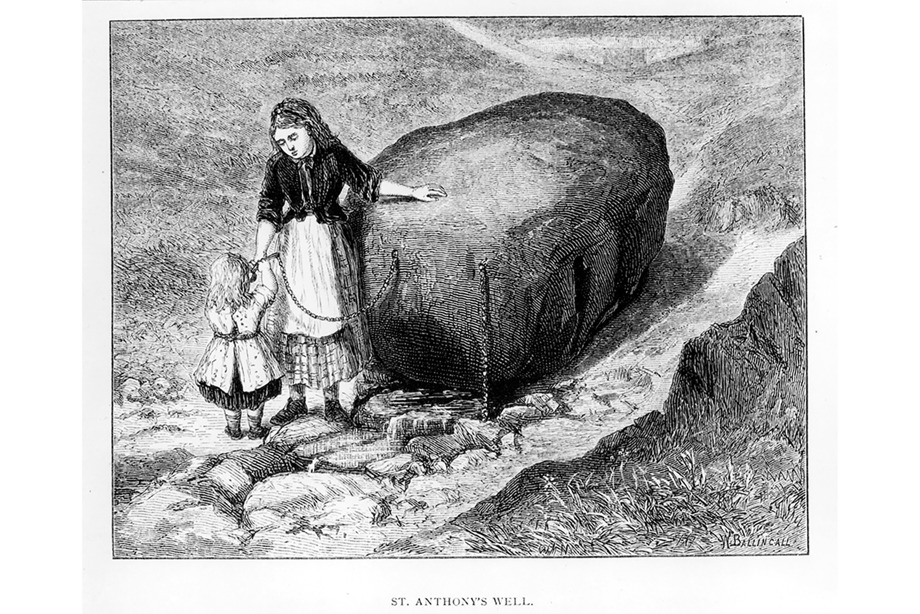

St Anthony's Well, Holyrood Park, Edinburgh

There are many ancient, sacred wells to be found in Scotland. Celtic belief in the magical or healing power of water led to a tradition of praying at springs, pools and wells to local nature spirits or goddesses.

Most of the wells were adopted after the arrival of Christianity and were dedicated instead to particular saints. We cannot say for certain whether the spring, now known as St Anthony’s Well, was considered a sacred place before the chapel dedicated to him was built on the hill above it in the 15th century. However, there is evidence of human activity in area we now know as Holyrood Park going back thousands of years and so the spring may have held earlier importance.

During the medieval period, some wells became places of pilgrimage and offerings would be left on altars that were sometimes constructed nearby. In the 1400s, pilgrims flocked to St Anthony’s Well in the hope that its water would cure their ailments.

The tradition of Clootie Wells – where, in the hope of healing, strips of cloth (‘clooties’) are tied to a tree branch beside a holy well – continues in some areas today.

The Story of St Anthony's Chapel at Holyrood Park, Edinburgh

Trudi uses British Sign Language (BSL) to tell the story of St Anthony’s chapel, its history and significance in the Edinburgh landscape.

Places for Prayer continued

Discover how the gradual adoption of Christianity was to transform Scotland’s religious architecture.